A Conversation with Shubigi Rao and Ute Meta Bauer

Artist Shubigi Rao and curator Ute Meta Bauer will represent Singapore at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia , which runs from 23 April 2022 to 27 November 2022. The team will mark Singapore’s 10th year participating in one of the biggest exhibitions in the art world. ART SG speaks to Shubigi Rao and Ute Meta Bauer on being selected for the Singapore pavilion.

Books rescued from the burning national library, still homeless 26 years later. Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina. Giclée print from The Wood for the Trees, 2018. Image courtesy of Shubigi Rao.

By Elaine Thanya Marie Teo

What are your thoughts on being the first all-female artist-curator team in the tenth year of Singapore’s participation in the event?

Shubigi Rao: Generally, only foregrounding gender can be uncomfortable, but I think in this case it is important. There are so many remarkable women artists in Singapore and to be the first all-women team selected is incredibly important to me for multiple reasons. While I was growing up, I didn’t see very many female-centred events or even solo exhibitions by women. On a personal level, I think to see the world shift this way and be a part of that shift is humbling and incredibly meaningful. It sends a signal that for too long we have regarded the default as being male. We don’t even notice if the line-up features one man after the other. I really hope this is just the beginning of the appreciation for the range and the diversity of works that women artists and curators bring into Singapore’s art scene.

Ute Meta Bauer: I have to say, in comparison with the art world, we saw more collectives, more community-driven works at the Architecture Biennale. It is not only gender that determines diversity. But I do remember that at the first Venice Biennale I attended 40 years ago – before I even studied art – I was particularly drawn to the Austrian pavilion that featured artists Maria Lassnig and Valie Export. It was outstanding at that time to see two women representing a national pavilion. Today this has fortunately become a lot more common; the next edition of the Biennale is directed by a woman, Cecilia Alemani. It’s about time for Singapore to feature one of their great female artists.

In Singapore’s cultural scene, you see quite a number of female cultural leaders. This is something I am amazed about. Rosa Daniel is the CEO of the National Arts Council, Chong Siak Ching is the CEO of the National Gallery Singapore, and Grace Fu served as Minister for Culture, Community and Youth.

Artistic team representing Singapore at the 59th La Biennale di Venezia. Image courtesy of National Arts Council (Singapore).

Can you tell us about your art practice, and how you came into studying this field?

Shubigi Rao: What defines me as an artist is my insatiable and unending curiosity about the world. Even though it can seem dire and overpowering, especially when one only looks at the world filtered through mainstream media. I think my natural inclination is to find hope in the quieter stories of persistence. I grew up curious about the natural world, and about the intellectual and artistic output of humans. To me, even though I wasn’t part of any great scene growing up – I was in an isolated part of the mountains in India – I felt connected to a greater sense of humanity through books, through the writing of other people, through the passion they poured into their writing and their art.

I happened to come to Singapore when there was a Lasalle College of the Arts graduation show and I saw the works and I knew this was where I belonged. It didn’t matter that I had previous degrees, I knew this was where I could finally follow my ideas through to completion, and so for me, my artistic practice has been defined less by formal notions of ‘going to art school and then you practice’. It’s more that being an artist allows me to practice across multiple fields, disciplines, and tackle very disparate ideas and fields of inquiry, and think through my ideas in multiple media.

My artistic practice is clearly defined now by one thing, understanding my place in the world and my responsibility to this planet. What I can try and do to make sense of what we’re doing here as a species, and what we mean to each other. I attempt this through multiple forms: writing, drawing, and film. I think films in particular speak in a very different way to us. We feel a sense of ownership over film. People are often hesitant to critique an artwork as passionately as they would debate the merits of a film. Everyone has an opinion about film.

I’ve always worked long-term, because ideas deserve time. The Venice project comes at a perfect moment because it is bang at the midpoint of my ‘Pulp’ project, which means I was already deeply involved with many different ideas.

The Singapore pavilion at Venice Biennale is making me rethink my approach as well. There are people who perhaps want to interact with this work in very different ways. This is not a work for an audience contained in a silo, in one place. This is the Venice Biennale; it is also for the world.

NAC has supported all the work that I’ve done since the beginning of my ‘Pulp’ project. I’m incredibly grateful that they are the commissioners of the pavilion, and it is hugely important that Singaporean artists get this kind of support internationally. Our previous artists have done exemplary work with the pavilion so it’s awesome that I’m part of that line as well.

What guides your curatorial process and how do you see this approach working in this partnership?

Ute Meta Bauer: What is interesting to me working with artists is how they view the world. I agree with Shubigi, artists tend to be underestimated in terms of what they tell us about the condition of the planet. An artist can provide us with a more distant perspective than reading the daily news. Art works have the ability to capture incidents in a way that allows us – the viewer – to grasp the gravity of certain occurrences. Shubigi is driven by an unstoppable curiosity and, like so many of us, she is interested in the impact of climate change, in national politics, but also in what is less visible, such as minority languages, autonomous archives, and the lives of people in different parts of the world.

I can relate to Shubigi’s practice as it comes very close to how I work as a curator. We both ask ourselves: what does a national (re)presentation mean? To participate in the Venice Biennale is different from putting up a show in an art institution. On top of this we have a global pandemic; what do you offer a public in such unpredictable circumstances? We indeed feel a strong sense of responsibility and pressure.

The place from where we embark and the site where we show are of course important, as we want to speak to both places and its people, beyond the international art community.

This participation allows us to spend time in the Veneto outside of the tourist season. Joining Shubigi on her artistic journey, I find it astonishing to see what she points to and what I haven’t seen prior. Indeed, Venice and Singapore have long been connected, for instance, through the Silk Road, but what can you do without creating a cliché, going deeper into the DNA of these connections?

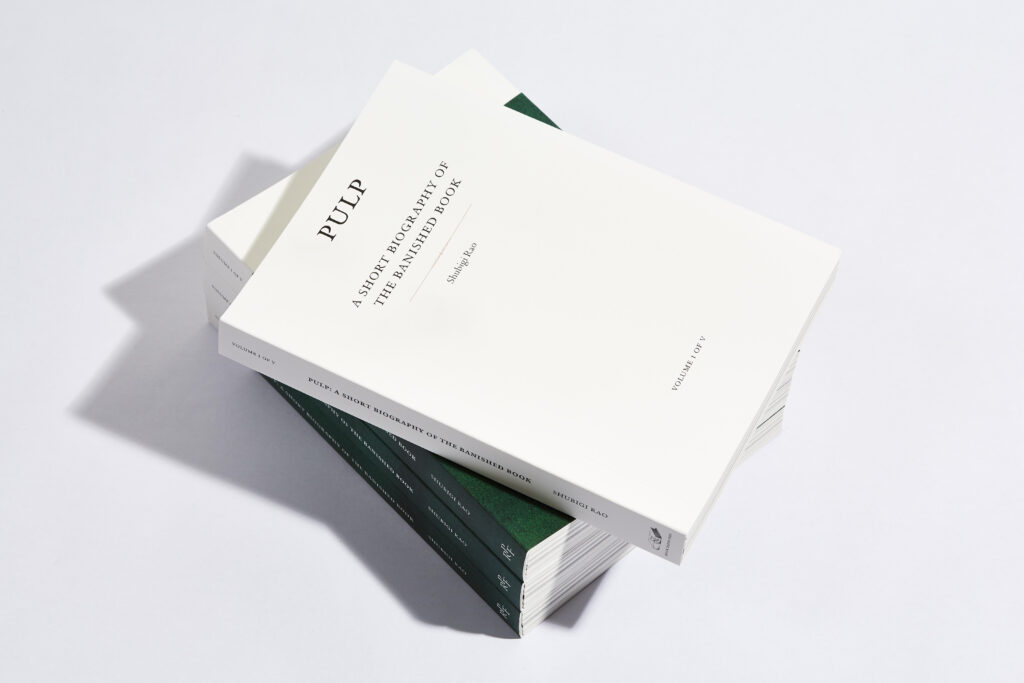

Shubigi Rao, Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book, Vol. I of V, Singapore: Rock Paper Fire, 2016. Image courtesy of SWELL.

The 59th edition of the Venice Biennale takes its title, The Milk of Dreams/Il latte dei sogni, from a children’s book written by late surrealist artist, Leonora Carrington. The curatorial premise draws upon the themes of imagination and transformation embedded within the book. How does this interplay with your oeuvre in its exploration into systems of knowledge and literature?

Shubigi Rao: When we did our proposal, it was before the announcement of the curatorial premise for the international exhibition for the biennale. National pavilions do not come under the overarching curatorial premise as such. Ute and I came up with our proposal for the Pavilion together. Still, it is kind of a lovely coincidence that there is a literary reference embedded in The Milk of Dreams. I think of course, one could say they are secret relationships but that’s also because I have a great weakness [laughs] in that I see connections between everything. This is useful because I can connect disparate bits of information and weave a narrative out of it. Naturally I see fragments and parts of Milk of Dreams that resonate with me. I think it’s always interesting for me to see the connections even if they are not obvious. I don’t always like to see a clearly drawn, unbroken line between things. I like it when there are echoes, when minds work on parallel tracks, they splinter and diverge, and come back to meet in unexpected places. Sometimes you can see hints of the unsaid, and that is more interesting to me.

Shubigi Rao. Image courtesy of Kathrin Leisch.

What can audiences look forward to at the Singapore Pavilion?

Shubigi Rao: I think there are two things I can say at this stage. Ute and I both care very deeply about the environment and the natural world. Climate change is a very huge topic under discussion but there are also other concerns and issues facing humans and the effects of our actions on the natural world, right? Ute and I have a very similar way of thinking about our sense of responsibility also, as an artist one can sometimes feel a sense of futility. In reality, there we are more effectual than we realise, once we delink that narcissistic need to immediately see the effects of our actions. Instead of constantly chasing positive results, we need to see that change occurs over time. Yet one of the quickest ways to reach people or to get an idea across people is through the arts. Ute is right, without this, we don’t have a way to speak to each other anymore. That’s why music, film, literature, visual art, they all communicate ideas so beautifully and with such power. And through a necessary discomfort as well. I know because I was shaped by that. I know it and I feel it in the core of my being.

Has the current pandemic and its global repercussions factored in the making of the artworks?

Ute Meta Bauer: When Shubigi and I discussed our proposal for the next edition of the Art Biennale, it was the beginning of Covid-19. We indeed asked ourselves: What can we do if we can’t travel, if no one can travel? How do we connect when we are disconnected? We both agree that the experience of art is important, but the condition of seeing art and travelling to places has changed. We were thinking among ourselves as well as in our team about how to reach people through art, if physical movement stays restricted. Shubigi and I believe in the impact of art, not just visual art, but theatre, literature, film, music and so on. There is a drive in us that wants to connect and comfort people in the moment of crisis. We debated a lot about humanity itself.

Shubigi Rao: As Ute said, how do the visual arts travel? How does a national pavilion have a presence there? How do you get the experience of a pavilion if you can’t physically visit it? For us these concerns propelled us to consider different ways of experiencing a pavilion. At least for me as an artist, I was really guided by Ute’s curatorial navigation. Some might call them problems, but I think for us there was an opportunity to rethink the way we would usually do things. I think the thoughtfulness required for every decision was necessary, and it has been an absolute privilege to work with Ute because it has reinforced my belief in how much power is embedded in an artistic action or artistic decision.

Ute Meta Bauer. Image courtesy of Christine Fenzl.

How has working on the 2015 Venice Biennale shaped the way you approach the upcoming exhibition? (Ute Meta Bauer was part of the US Pavilion of the 2015 edition of the Venice Biennale, featuring artist Joan Jonas)

Ute Meta Bauer: If you’re selected as an artist for a national pavilion, it marks one of the big highlights of an artist’s career. As a curator, you want to support the artist in every aspect as good as you can, but the role of the curator means also to understand the entire context of such a presentation. Serving as a co-curator for Joan Jonas and the US pavilion was such an honour. Joan pointed to the fact that there are so many artists living in the United States, and it felt odd to her representing such a huge country while so many of her peers have not been selected. It’s a big pressure for the artist, and to me the role of a curator is to be there, and to allow the artist to concentrate on her work. My experience from 2015 is the awareness of the complexity that comes with Venice.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: ELAINE THANYA MARIE TEO

Elaine Thanya Marie Teo is a writer, and researcher based in Singapore. She holds a MA in Asian Art Histories from LaSalle College of the Arts, and a BA in Psychology from Nanyang Technological University. Her research has focused on the intersection between identity, and the visual arts with a particular eye towards deconstructive theory. In 2017, She served as a panellist in Singapore’s Third Graduate Conference in Visual Culture. She was also a speaker at the State University of New York’s Art Conference in 2018. As part of Tekad Kolektif, Elaine Thanya Marie Teo is the 2021 recipient of the Objectifs’ Curator Open Call.