Home / A Conversation with Alex and Johnny Turnbull

Share this article:

Unfazed, Alex and Johnny blazed their trails, channelling their creativity into martial arts, skateboarding, music, and filmmaking. Their band, 23 Skidoo, broke new ground with its genre-blending mix of post-punk, dub, industrial, and world music, often incorporating ambient recordings, unconventional sounds, and tribal percussion. Meanwhile, as a founding member of the International Stüssy Tribe, Alex became part of a vibrant network of creatives that helped propel streetwear into a global cultural force.

Since 2006, the brothers have also taken on the mantle of managing their late parents’ estates, working tirelessly to cement Kim Lim and William Turnbull’s rightful place in the annals of modern art. ART SG caught up with Alex and Johnny on the eve of the highly anticipated homecoming exhibition, “Kim Lim: The Space Between. A Retrospective” at the National Gallery Singapore—the most comprehensive museum survey of the pioneering artist’s work to date— to discuss this milestone, their parents’ legacy, and its intersection with their creative paths.

Johnny (Left) and Alex Turnbull (Right) at the afterparty of the opening of Kim Lim: Space, Rhythm & Light, The Hepworth Wakefield, United Kingdom, 2023. Photo courtesy of Alex Turnbull.

How has growing up as the sons of Kim Lim and William Turnbull influenced your artistic journey?

Alex Turnbull (AT): Our parents’ generation rarely spoke about themselves, so we knew little beyond their occasional anecdotes. It wasn’t until I made Beyond Time—a documentary about Bill [William Turnbull]—that I realised this experimental drive is in our DNA; it’s something cellular. 23 Skidoo was an avant-garde, experimental band, seen as “a musician’s musician’s band,” but our parents had been pioneers of that creative energy long before we arrived. We’ve always been outsiders, much like them. It wasn’t until we took on managing their estates that we truly understood how profoundly the osmosis of growing up around them had shaped us.

Johnny Turnbull (JT): It’s this innate urge to create purely for the sake of it, without concern for the outcome or reward. I love making things, especially music. Recently, I’ve been reflecting on my approach to music, and there’s something almost sculptural about it—starting with an idea, laying it down, and then going back to mould, shape, refine, and even remove parts. A lot of this is due to the technology we have now. Recording has evolved so much with computer programming; you can record live, sequence everything, and visualise it on the screen. It’s almost like crafting a piece of sonic sculpture.

How has the experience of managing your parents’ estates been, and what does it mean to see their legacies finally gain the recognition they deserve, largely due to your efforts?

AT: In 2005, when Bill was about 83, he asked us to assist with managing his studio. Until then, we hadn’t imagined stepping into that role as we were fully immersed in our creative work. But it was clear that it couldn’t be delayed—it had to be done. His influence as one of Britain’s most significant post-war artists was waning, and we knew it was vital to preserve his legacy. His decision to take a firm stand against the Royal Academy – refusing to join and viewing them as adversaries of modern art early in his career – made our task even more difficult. We ended up handling almost everything ourselves.

For a long time, our priority with Mum’s work was preservation. Whenever one of her pieces came up for sale, we would buy it back, holding onto it until the right moment for reintroduction. Her 2018 exhibition at STPI in Singapore was pivotal, marking her first show in Asia since her passing in 1997. In the same year, her exhibition at S|2 Gallery London, curated by Bianca Chu, finally garnered the recognition and value it deserved, thanks to Bianca’s deep understanding and appreciation of the pioneering nature of Kim’s work.

JT: We often relied on instinct when managing Kim’s estate. Operating independently, without any gallery affiliation, we focused on cultivating strong relationships and securing institutional placements. Support from people like Magnus Renfrew, Co-founder of ART SG and a long-time family friend, has been invaluable. Managing both estates has taught us different approaches, and we’re continually learning how to balance integrity, legacy and the commercial side of things. It’s a delicate process, and getting it right every time can be tricky.

AT: Seeing our parents finally receive the recognition they so rightly deserve has been an emotional journey, especially with Mum’s homecoming exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore. It is the culmination of years of hard work.

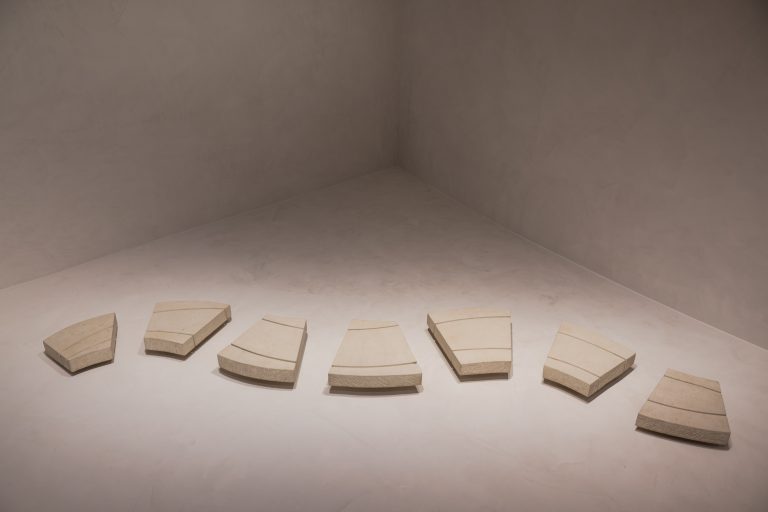

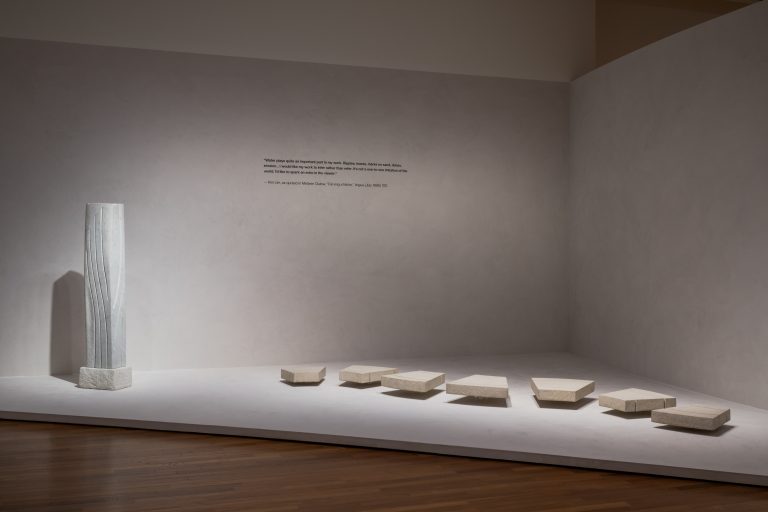

Installation view, Kim Lim: The Space Between. A Retrospective, National Gallery Singapore, 2024. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore. © Estate of Kim Lim. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

Managing an artist’s estate is a huge task, let alone handling two—especially when they’re your parents. Does it ever feel like a massive weight on your shoulders?

AT: It’s a huge responsibility to get it right and do justice to their legacy. Establishing the Turnbull Studio in London in 2008 was a vital step. Making their works accessible to the right people at the right time was crucial. It can take years—sometimes four, five, even eight—for things to come to fruition. But you have to plant those seeds and be patient. It’s rewarding to see that the sapling has grown into a tree and is finally blooming.

JT: At times, the workload feels endless. The archiving process we’re undertaking now is a monumental task. Even after twenty years, we’re still discovering previously unseen works on paper. There’s also the financial aspect, which is substantial costs for storage and insurance.

AT: But just like in music, Johnny and I have complementary skills, which makes working together so effective. Our shared history of skateboarding and creating music has laid the groundwork for us to tackle this together.

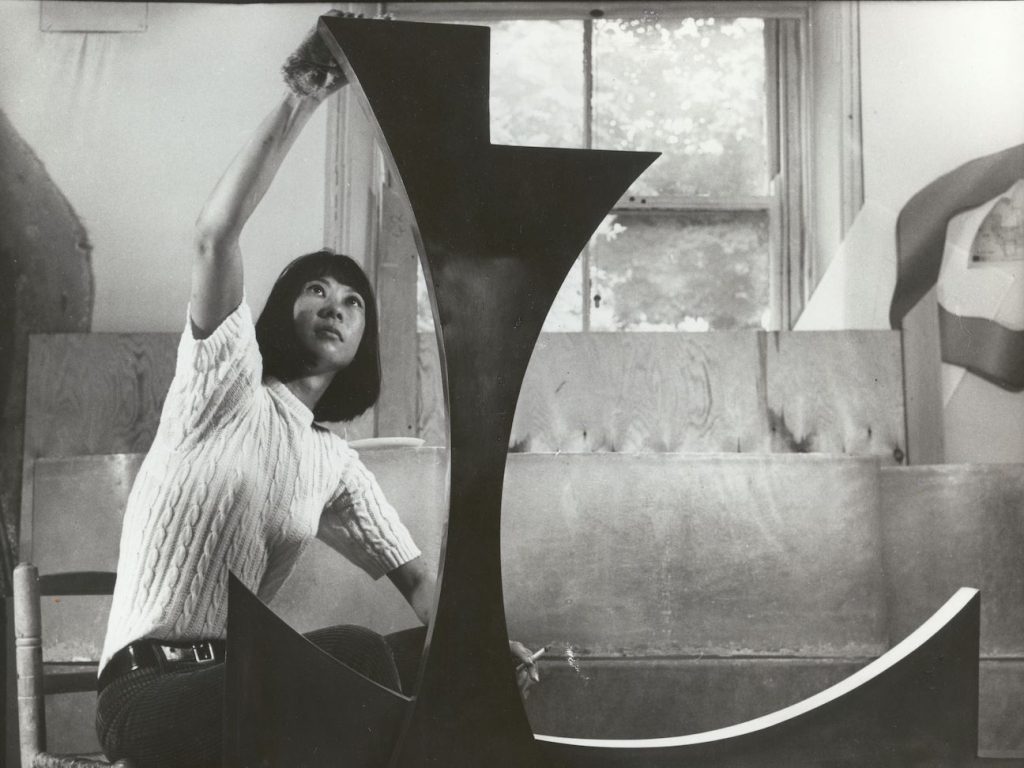

Kim Lim working on Twice, 1968. © Estate of Kim Lim. All Rights Reserved, DACS. Photo: Jorge Lewinski. © The Lewinski Archive at Chatsworth. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images.

Kim was a significant figure in the 1970s British art scene, recognised as the only female and non-white artist in the 1977 Hayward Annual. However, after her passing in 1997, her work slipped into relative obscurity. What specific challenges have you encountered in reviving her legacy, and how have you navigated them to ensure her contributions are recognised once again?

AT: The art world today is very different from the one we grew up in—it’s much more commercialised. We’ve tried to manage both their estates in a more old-school, low-key manner, steering clear of over-hype. Our approach reflects who they were as people and artists. But when you’re not out front shouting, it can feel like no one’s paying attention. Sometimes, it can feel like pushing a rock uphill – it moves up, then rolls right back down on you.

JT: We believe in the integrity and strength of the work standing on its own merit rather than using hype to gain attention. Navigating this landscape while maintaining integrity is challenging, but it’s something we’re committed to.

AT: That said, it’s been amazing to see that after 15 years of pushing this rock uphill, it’s finally gaining momentum. I think it’s partly because of who Mum was and partly thanks to the art world’s growing emphasis on recognising Asian and women artists who have long been left out of traditional art history narratives.

I read that Kim is one of the most collected artists in the British National Collection, second only to Anish Kapoor. However, as curator and writer Hammad Nasar noted, being in collections doesn’t always guarantee visibility.

AT: Yes, she’s one of the most collected but the least displayed. It’s nice to see that it’s changing now.

JT: She has two works in the new Tate Britain display, which is quite unprecedented.

AT: She’s exhibited right next to Isamu Noguchi at M+ in Hong Kong, which is incredible. We’re also collaborating with two other major institutions that we can’t reveal yet—one in the Middle East and one in the United States.

Kim Lim’s studio at her home in Camden. © Estate of William Turnbull.

How do you view the relationship between Kim’s sculptural work and her printmaking practice?

AT: Just like painting and sculpture were equally important to our father, printmaking was just as significant to Kim as her sculpture. Although printmaking is often undervalued due to the art world’s tendency to equate worth with price, it was an integral part of her practice. There is a strong link between carving and printmaking. Printmaking involves taking away—scoring, etching, and removing material. This emphasis on reduction is a recurring theme throughout Kim’s work.

Growing up, you often helped in Kim’s studio at home. What was that experience like, and how did it shape your understanding of her artistic vision? Did you spend much time in your father’s studio?

JT: Kim’s studio was located on the lower ground floor of our house in Camden. As kids, we would help ink the etching plates and turn the printing press. It was a fascinating environment to grow up in, filled with all sorts of intriguing objects to explore. The physical effort she put into creating her stone works in her later years was astonishing, especially since we were her only assistants in moving those heavy pieces. And when it came to crafting the works, it was all her—chiselling and filing by hand. Witnessing that level of dedication firsthand was truly awe-inspiring.

AT: With Mum, we have a deep physical connection to her work. On the other hand, Bill kept his practice private and separate.

The chiselling and hammering must have created quite a noisy environment, a sharp contrast to the serene way her work is displayed in museums today. As musicians, I’m curious—how did growing up surrounded by those sounds influence your approach to music?

JT: The acoustic environment around the house had a huge impact, especially the rhythmic, metronomic sounds she made while working. Some of the sculptures themselves produced incredible sounds. I once created a rhythmic loop just by tapping on one of Bill’s pieces—it made this fantastic, resonant tone.

AT: I think our parents’ influence came more from what they demonstrated in their daily lives—their integrity and unwavering commitment to their creative visions and paths. Though they were very different in personality, they shared a deep commonality. As a drummer and percussionist, and with rhythm being such a central element of our music, it’s likely I was shaped by the acoustic environment at home. Johnny was always the more musical one, playing guitar, but he’s also an excellent percussionist.

I’m struck by the repetition and rhythmic quality in Kim’s work, which seems to mirror music, with its rests and pauses inviting reflection and anticipation. Was music a big part of your household growing up?

JT: Our parents had an eclectic record collection that spanned jazz, ethnic, classical, and modern music. I was particularly fascinated by their African and Indian music albums, which featured incredible soundscapes created with traditional instruments. Access to anything was extremely limited back then. Access to music was extremely limited back then—there were only two TV stations and very few radio stations! Exposure to such diverse and sophisticated music through our parents’ collection was crucial in broadening our musical horizons.

AT: Bill was the real music enthusiast. Mum, on the other hand, always went about her business in a very quiet, low-key manner. We inherited their old record player – a big black box – and a few records that had a significant impact on us during our early childhood. Revolver by The Beatles and Their Satanic Majesties Request by The Rolling Stones (I still remember the 3D cover, which felt so modern at the time) are the ones that stand out most. Later, I particularly recall a shakuhachi flute record, an Indian Raga Shree album, and their jazz collection, though I think we only truly appreciated those in our late teens

William Turnbull with Sculptures, 1959. © Estate of William Turnbull. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022. Photo: Kim Lim

William was associated with various art movements, from the Independent Group and ‘The Geometry of Fear’ to Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. While he built friendships with artists like Eduardo Paolozzi, Alberto Giacometti, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, he maintained a distinct and solitary practice, positioning himself simultaneously at the centre and the fringe.

JT: He never saw himself as part of any particular group or movement—he simply wanted to be an artist, much like Kim, who resisted being defined by her identity as an Asian woman. Although often pigeonholed as a sculptor, Bill explored a range of mediums, from watercolours to painting. Viewing these works alongside his sculptures reveals a clear continuity and the transitions in his artistic journey.

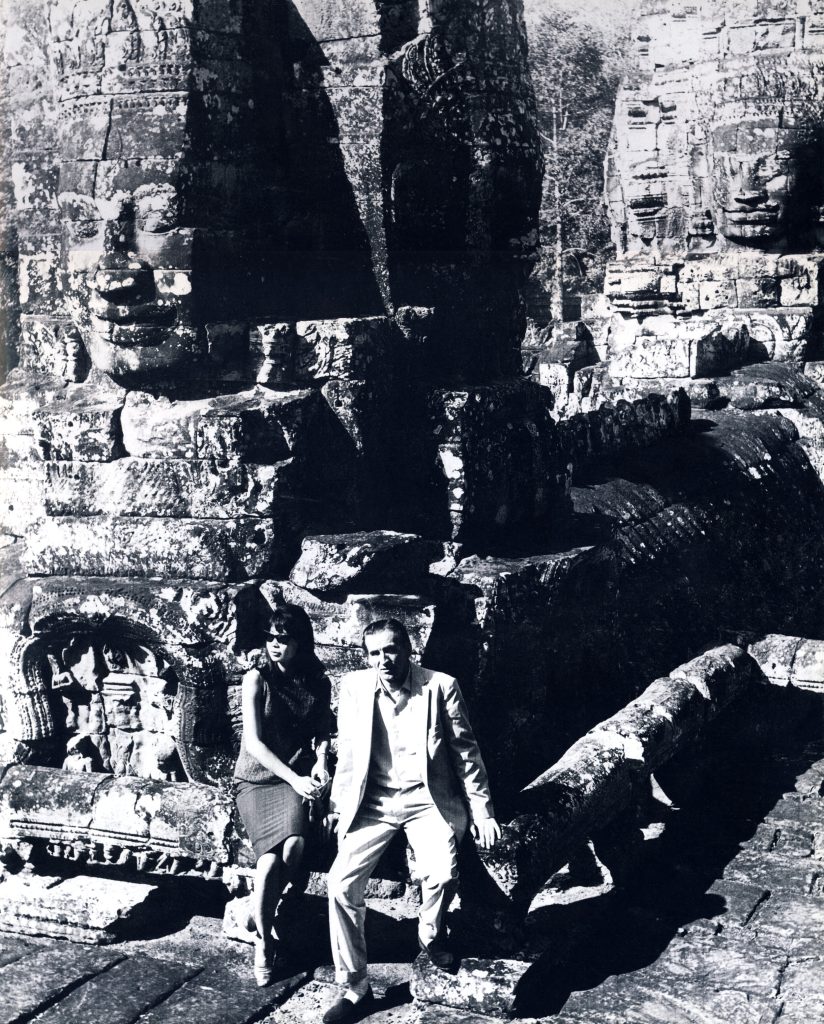

Kim Lim and William Turnbull at Angkor Wat, Cambodia, 1962. © Estate of William Turnbull.

What stood out to me most about the photographs of their travels, especially in Asia, was how Kim and William drew from the past to envision the future. This idea is evident in their work, which effortlessly transcends spatiotemporal boundaries.

JT: They both had a strong interest in the visual vocabularies of diverse cultures, both ancient and contemporary, which greatly enriched their creative expression. These interests ranged from everyday objects to architectural elements, such as the patterns of roof timbers or the lattice structure of bamboo scaffolding in Asia, to monumental sites, such as Angkor Wat and the Pyramids of Egypt, as well as prehistoric flints and Cycladic figures.

The current exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore includes excellent examples of Mum’s photography that clearly show the influence of her travels. In one vitrine, a photo of Trengganu III (1968) is displayed alongside the etching plate from Ring Engraving (1970), both of which echo a shape later seen in her stainless steel sculpture Ring (1972). Above, a photo of a temple garden with semi-circular stone patterns hints at a possible source of inspiration.

Titles like Samurai (1961), Ronin (1963), Narcissus (1959), Centaur (1963), and Pegasus (1962) reveal the influence of both Asian culture and Western mythology. Geography and nature also played key roles in her work, as seen in sculptures like Irrawaddy (1979) and the Trengannu series (1968).

AT: Mum was an incredible photographer, and many of the best photos of our father were taken by her. It’s remarkable to be able to illustrate the film I’m making about her using her photographs, with Johnny composing the music.

Reflecting on the title of Kim’s Singapore exhibition, The Space Between, I couldn’t help but think about how she and William, as two remarkable artists, shared the same space while maintaining their own distinct identities. How did they create room for each other to thrive creatively?

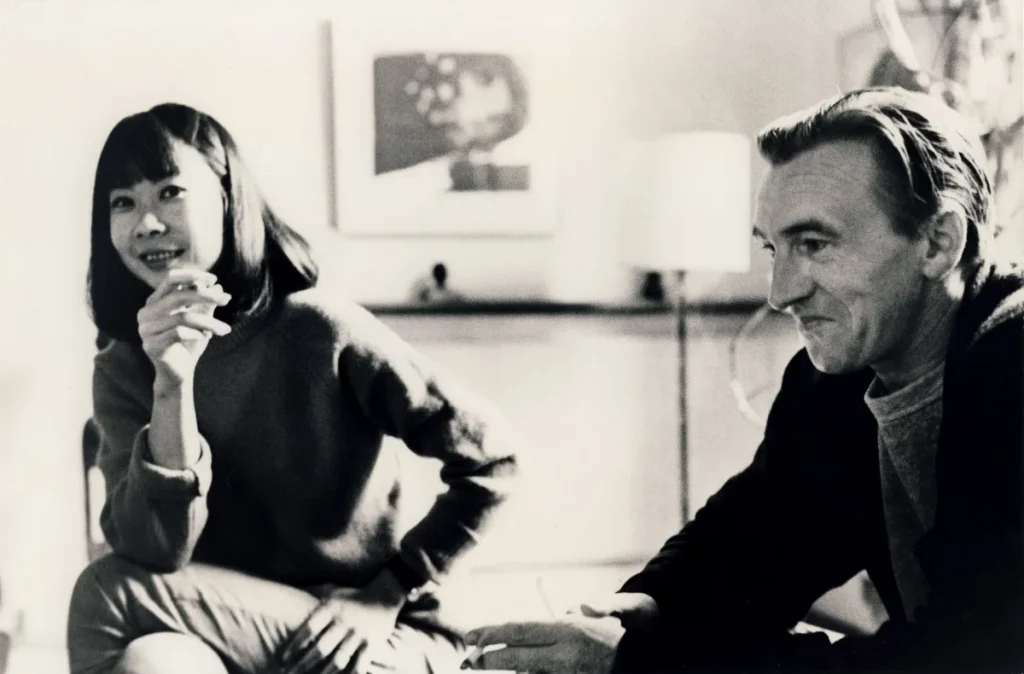

AT: There was an incredible respect and love between them. You see in these amazing photos of them when they were young—both striking individuals. There was clearly a physical attraction but also a profound intellectual and artistic connection. They were drawn to each other not just as people but as artists, deeply inspired by each other’s work. Bill always said she was the best artist he knew, and I think he found as much inspiration in her work as she did in his. Though there are intersections in their art, their work remains distinct.

It’s fascinating that my parents came from such different backgrounds—Bill from a shipyard in Dundee and Kim from a well-off family in Singapore. Despite growing up in environments without art, they were somehow put onto this planet to do precisely what they did.

Kim Lim and William Turnbull at home in the 1960s. © Estate of Kim Lim. All Rights Reserved, DACS. Photographer unknown.

As both a female and foreign artist in Britain, Kim faced a form of double othering. She notably declined an invitation from Rasheed Araeen to participate in “The Other Story,” a seminal 1989 exhibition at Hayward Gallery which focused on Asian, African, and Caribbean artists in post-war Britain, as she didn’t want to be “othered”. How did Kim navigate the “in-betweenness” of being both part of and outside the British art establishment?

AT: Kim infused her art with Asian cultural elements during a time when Western influences—particularly American and British—dominated, and Asia was seldom viewed as a source of inspiration. She did so with subtlety, refusing to be defined by her gender or race, preferring to be recognised simply as an artist. Both she and our father operated on the fringes of the art world—he, an uncompromising Scot who resisted being labelled a British artist, and she, rejecting labels linked to her Asian heritage or gender, especially when recognition for either was scarce. For them, it was crucial that their work be evaluated purely on its own merit. Their philosophy was straightforward: “This is my art. Take it or leave it, but judge it for what it is.”

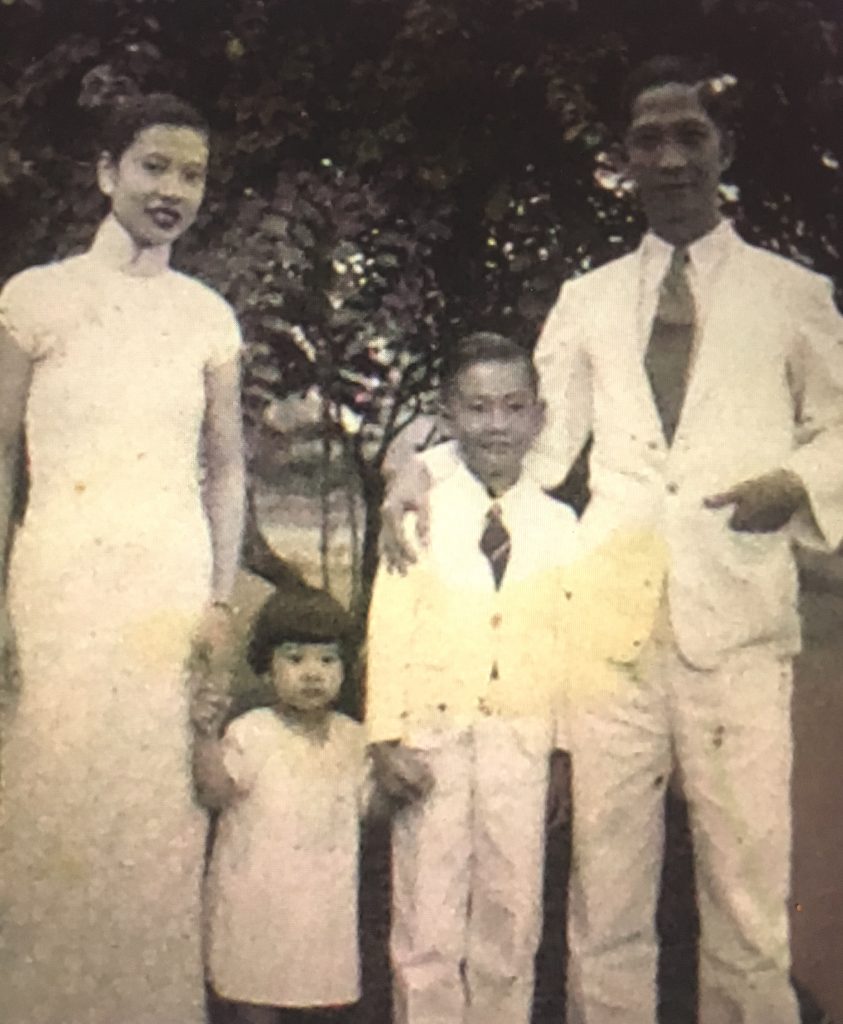

There’s a misconception that Kim renounced her Singaporean identity when she left at 17, but it was always about her art. She couldn’t have achieved what she did if she’d stayed, so she went abroad to pursue her art. It’s important to understand that being part of the diaspora often makes you more aware of your identity, especially in those days. She was always deeply conscious of her identity and stayed connected to her Singaporean roots.

Kim Lim with parents (Lim Koon Teck, Betty Lim) and brother Han. © Estate of Kim Lim.

What gives both Kim and William’s work a timeless quality, making it as impactful today as it was when it was first created?

JT: I think it’s the integrity and authenticity they brought to their work—it’s genuine. There were no shortcuts in their journey; everything was earned through sheer dedication and perseverance. Their mastery didn’t come overnight but was refined through countless hours of relentless effort and experimentation in the studio. That level of commitment and devotion to their craft continues to resonate across generations.

What new narratives do you hope Kim’s current exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore will inspire about her diverse body of work, particularly in relation to the histories of sculpture in both Singapore and Britain?

JT: I’ve been reflecting on creativity in a world that demands constant attention and thrives on instant gratification. When these works were created, there was no expectation of immediate recognition; the true reward was in the process itself. It’s a reminder of the dedication required to create something meaningful, even without applause. It prompts us to consider how we spend our time and what truly gives life meaning. Their work is about making sense of the world and expressing what words cannot. That’s the alchemy of great art—to transform ideas into objects with a gravity that draws us in and invites reflection.

Installation view, Kim Lim: The Space Between. A Retrospective, National Gallery Singapore, 2024. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore. © Estate of Kim Lim. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

“Kim Lim: The Space Between. A Retrospective” runs from 27 September 2024 to 2 February 2025 at the National Gallery Singapore’s Singtel Special Exhibition Galleries 2 & 3. Learn more here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: YVONNE WANG

Yvonne is an art writer and the Singapore desk editor for ArtAsiaPacific. She regularly contributes to various art publications and collaborates with art platforms to craft bespoke content. Her writing has been featured in ArtAsiaPacific, Asia Art Archive’s IDEAS Journal, Art & Market, The Art Newspaper, and other notable outlets.

Share this article: