Home / A Conversation with Htein Lin and Louis Ho

Share this article:

Another Spring

Htein Lin

Curated by Louis Ho

Richard Koh Fine Art Singapore

18 February – 19 March 2022

Louis, could you give us a brief background of your engagement with the contemporary art of Myanmar, and why you were excited to curate this show by Htein Lin?

Louis Ho: My involvement with Myanmar’s contemporary art scene dates to the fifth edition of the Singapore Biennale in 2016, ‘An Atlas of Mirrors’– though personal interest precedes that! As part of the curatorial team, I was responsible for two Burmese projects in the exhibition, one of which was Htein Lin’s Soap Blocked, a floor-bound installation comprised of numerous carved blocks of soap arranged in the geographical shape of Myanmar itself. It spoke to the years he spent behind bars, incarcerated on trumped-up charges. Since then, I’ve also put together a small show of contemporary Burmese art at Richard Koh Fine Art in 2020, which included the work of Htein Lin and performance artist Aye Ko, as well as Soe Yu Nwe, Nge Lay, Aung Ko and Richie Htet, among others. I’ve also worked with Shwe Wutt Hmon, an artist and photographer who won the first prize in the Still Images category of the inaugural Julius Baer Next Generation Art Prize in 2021.

‘Another Spring’ represents the first opportunity we’ve had to present contemporary Burmese art here in Singapore since the military coup occurred last year, a year that has proven catastrophic for Myanmar. Htein Lin’s work is urgently topical. His longyi paintings address the country’s ongoing conflict, which has seen more than a thousand casualties to date, and thousands more detained and tortured. It’s the sort of exhibition we need right now.

Htein Lin, this solo show at RFKA makes reference to a street installation you enacted last year, during the height of protests against the military coup. The civic demonstrations were widely reported in international media, and several artists were involved in the protests as well, with many vocalizing their resistance through their art. Can you share how these developments in Myanmar influenced the premise and form of this exhibition, and the message you hope to convey?

Htein Lin: Back in 2018, I started to explore the Myanmar superstition about women’s clothing, and the idea that contact with it, or walking under it, could affect a man’s hpone. Hpone is a difficult idea to translate. It suggests male strength, or superiority. I think it is a taboo that historically existed in the region and has died out, but in Myanmar a significant part of the population, particularly in rural areas, believe in it. I painted a series of portraits of women, each one in their longyis, and asked them to write a text on the portrait expressing what they felt about the taboo. These portraits were shown in Hong Kong, Yangon and Tokyo as ‘Skirting the Issue’.

My May 2019 show in Yangon became notorious, and generated big arguments on Facebook, including whether this was really a Buddhist belief, or just a patriarchal one. I was threatened and trolled by members of the ma-ba-tha nationalist Buddhist movement. The police even came on the last day of the show and asked me to take it down as they were worried about trouble.

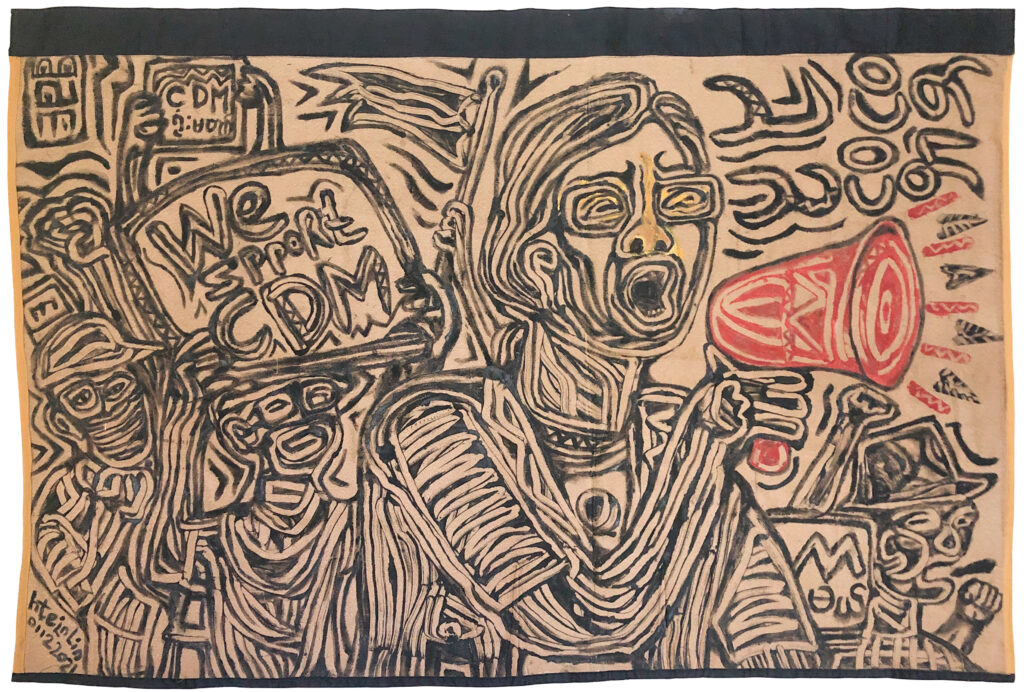

When the demonstrations against the military regime started in February 2021, and the clampdown began in early March, people started realising that if they hung women’s clothing up across the street, it would give demonstrators more time to escape, as the soldiers didn’t like to go underneath these clotheslines. So, I decided to create an artwork as a first line of defense. It lasted for about two weeks before it was ripped down by the military and burned. At that point in March, it was already getting dangerous to be out on the streets, and I am getting too old to run fast, so I decided to retreat to my studio and paint some scenes from the Spring Revolution. Again, I used old longyis as my canvas– it was a habit I picked up in prison when I had no choice, but it’s also a useful medium to fold up and put at the back of the drawer. This painting sews together six panels as a celebration of the multi-coloured bravery of peaceful demonstrators across the country.

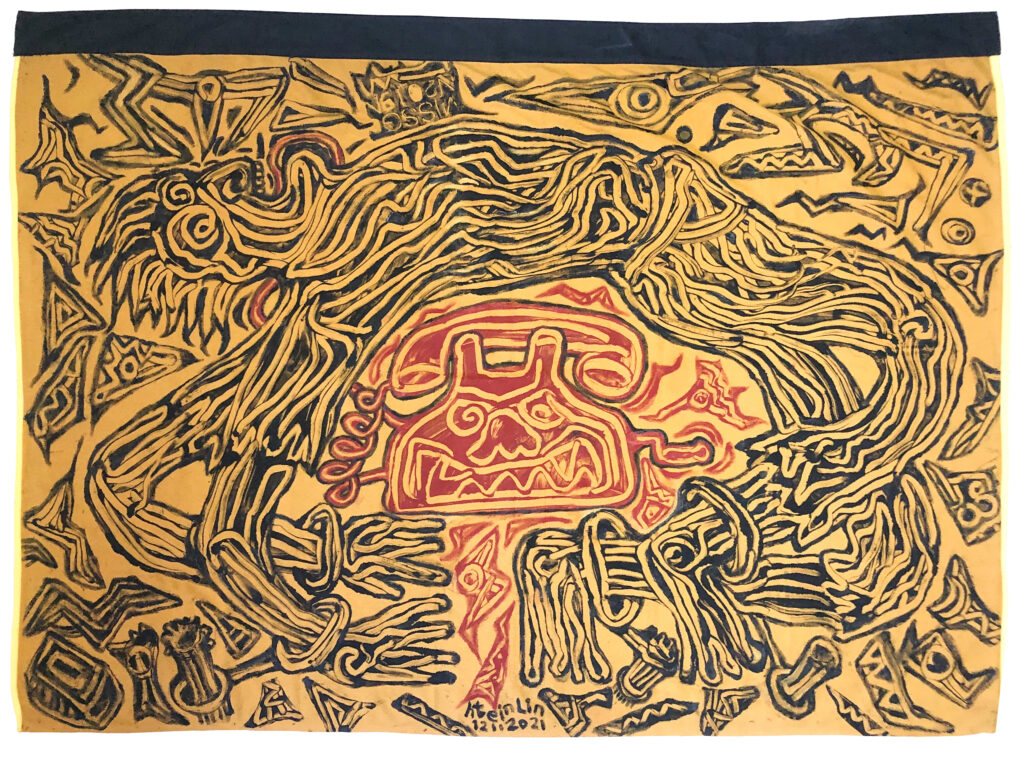

A few months later, when the opposition took to the jungle and took up arms, I was reminded of how I had done the same thirty years earlier, and how it ended badly when an internal leadership struggle led to torture and execution. I wanted to share my experience from that period with the Gen Z rebels and warn them not to end up on that path. So that was where the series, “Instruments of Torture” (2021), came from, again on longyis.

There is a long history of artistic dissent against the junta in Myanmar, and artists also have to contend with strict censorship policies. Htein Lin, you have been involved in a number of projects that enmesh art with political action and everyday life, by engaging in what has been termed a “politics of the daily”. One such project was Mobile Market / Mobile Gallery (2005), which you initiated together with artist Chaw Ei Thein. How do you feel this current body of works extends this narrative, or do you feel your response has evolved in view of the ongoing situation?

Htein Lin: There are two angles to this. Artists have drawn material from the political situation and turned it into art and a means to provoke discussion. Our street performance Mobile Market, Mobile Gallery in 2005 was intended to stimulate thinking about the value of money and art against the background of 30% annual inflation. The authorities didn’t know what to make of it, so they decided to detain us for a few days, and we had to explain Performance Art 101 to several shifts of Special Branch personnel.

Sometimes opposition forces have harnessed art and creativity to strengthen their movement, such as the 88 Generation in 2007 and even more so during the Spring Revolution, in which each day’s demonstration was inspired by a different theme.

In both of your opinions, what has changed in the Myanmar art scene since your early days of involvement? Are the younger generation of artists still interested in the same issues? How similarly, or differently, are they approaching these?

Htein Lin: My early days as an artist came around a turning point for Myanmar politics from a one-party socialist system to the market economy. During the early 1990s, there was a lot of art criticism in Myanmar language art and literature magazines such as Pinleh (The Sea), Tharaphu (Crown) and HanThit (New Style). We artists were reading about postmodernism and conceptual art, and it was inspiring us to approach new forms of art beyond painting, such as performance, installation, and video art.

Nowadays, the new Generation Z artists have had their own political transition, albeit backwards. I think they are currently struggling to come to terms with that, but as we saw during the Spring Revolution, there is lots of creativity and there are new digital forms of expression that we didn’t have, so I hope that this period will be remembered for generating a new wave of artists.

Louis Ho: Htein Lin is certainly right about a wave of creativity in Myanmar. My engagement with Burmese art is fairly recent, but being introduced to the country’s cultural scene was something of a revelation. There is alternative music, punk rock, film, street art, comics– in addition to familiar contemporary art mediums such as performance and installation. The graphic arts, for one, have had a long history in Myanmar. Htein Lin’s time in a student rebel camp in the early 1990s has been captured in a graphic novel, Pajau, published in 2020, in collaboration with Burmese comic artist Wooh. Wah Nu– herself the daughter of acclaimed filmmaker, Maung Wunna– channeled the colour palette of cheaply printed comics, popular with children of past generations, in a recent series of cloud paintings. The Myanmar Diaries, a documentary film by an anonymous collective that portrays the atrocities perpetrated by the military government in the past year, has just won the Amnesty International Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival, while Midi Z, a filmmaker of the Sino-Burmese diaspora, has paid tribute to the experience of ethnic minorities in Myanmar in The Road to Mandalay (2016).

What do you think is the role of the Myanmar contemporary artist now? Should art exist separately and objectively from the ongoing situation, for example acting as commentary but from a distance? Or do you feel artists should take a more involved stance as artist-activists?

Htein Lin: I wouldn’t want to be prescriptive. For artists– other than the purely decorative– there will always be some elements of both, and artists will find the right mixture for the right time. What matters most is that artists need to create what they believe in.

Htein Lin, you practice vipassana meditation daily, and often incorporate Buddhist themes and stories in your art. Could you say a little more about why you practice this form of meditation, and tell us more about your works that make reference to Buddhist philosophy? How is Buddhism situated against the activistic part of your practice?

Htein Lin: I see my meditation practice as more about reflecting on, and acting in line with the laws of nature than about Buddhism per se. It gives me balance in a complex world and allows me to approach problems calmly. It helps me understand myself and through understanding who I am, I can better understand others and wider society, including during this turmoil. Meditation also makes me more aware, and examine concepts in greater detail, so I hope it takes my art beyond the superficial and allows me to observe in greater depth.

Htein Lin’s approach to artmaking is very much informed by the exigencies of his time. Louis, why did you feel a need to highlight his work, and how do you feel his practice should be approached by viewers particularly during this specific moment?

Louis Ho: I’m not sure it is his personal voice that’s being foregrounded here. This is certainly an exhibition of Htein Lin’s work, but it almost feels as if what’s essential is its reflection of what has transpired in Myanmar in the past year, filtered through a personal lens. The show also addresses the history of conflict that has beset the country in the twentieth century, which, of course, Htein Lin alludes to in the ‘Instruments of Torture’ series, captured in the graphic novel, Pajau (2021). ‘Another Spring’ is a two-pronged show: it highlights the recent calamity in the country, but also ties a historical thread to the events of the 1988 uprising and its aftermath, in which Htein Lin was likewise a participant. It offers a direct, microcosmic representation of current events in Myanmar, as well as their historical context, made visually accessible, in a very personal, visceral way, to Singaporean viewers who may otherwise be unfamiliar with both.

In your opinion, what is unique about the art scene in Myanmar, vis-à-vis the rest of the region? And what are some similarities or connections that the Myanmar art scene shares with neighbouring art ecologies? What can we look forward to in the months or years ahead?

Louis Ho: A lot of what’s different about Myanmar’s contemporary art scene is largely due to the socio-political realities of the past several decades, for better or worse. The ecology is small, and largely centred in Yangon. There were few spaces for the display of contemporary art, even pre-pandemic– and not much of a commercial market as well, according to those in the know. Perhaps the issue is less about absolute differences or unique areas, but rather stages of development. The art scene in Myanmar can only develop in tandem with what the economy and infrastructure can sustain, and that, unsurprisingly, has lagged behind its more developed neighbours in Southeast Asia. If a comparative historical study is made, the scene in Myanmar in the past decade may well bear similarities to that of Vietnam in the early years of Doi Moi, for instance. (I’m not sure if that would turn out to be true, but it’s possible, even plausible.) That being noted, contemporary Burmese art is gaining increasing traction outside the country: the Asia-Pacific Triennial, for one, has consistently maintained Burmese representation in recent editions, as has the Singapore Biennale, and various galleries in the region, particularly in Singapore and Bangkok, have devoted programming to Burmese art and artists. The cultural links between Myanmar and SE Asia certainly exist, but the coup has disrupted so much of the economy and everyday life there, and who knows how many more years it’ll take for the country to rebuild itself… In the meantime, we can only do what little we can on the peripheries.

Share this article: