Home / A Conversation with Ken Hakuta

By Tan Siuli

Hello Ken, what was your relationship with Paik, and what was it like growing up with him as a major influence in your life?

Ken Hakuta: Let me tell you, it was a really interesting thing being Nam June Paik’s nephew. He was a really good uncle – we used to call him “my crazy uncle”. Why was he crazy? Not because he destroyed pianos at performances – nowadays many musicians do that, but you have to remember back in the ‘50s and ‘60s that was pretty new – but he would tell my mother, “Let Ken watch more TV!”. And he convinced my mother to buy me a new television set! I was made to take piano lessons at home, like many Asian families, and I was neither good at it nor liked it. But one day my uncle had the piano brought to one of his performances, and it never came back. Because it got destroyed at the performance! So, no more piano lessons. I thought: “What a great uncle!”

It was really fun, and beyond my wildest imagination, I’m sure it opened up my mind. I hung around a lot of artists. We would very often, for example, go to visit Christo and Jeanne-Claude. They were very good friends, and I remember Jeanne-Claude saying, “Ken, we are always going to be starving artists, so you go and make lots of money, and help us!”. I was just a 14 year old boy and Jeanne-Claude would say things like that. Yoko Ono was around a lot, and I think I first met her when I was ten, way before John Lennon, when she was married to an American artist called Anthony Cox. And John Cage would visit. I remember he had very heavy footsteps. He was really loud, and he would scrape the floor a lot. It was like sound art! One time I was trying to sleep, he visited, and I thought, what a pain! John Cage is here and he was so loud I couldn’t sleep. This was in Nam June’s illegal loft in Soho – back then, they could work there but not stay there, They all did anyway. Because of zoning, they couldn’t have a kitchen, for instance, so they washed their dishes in the bathtub.

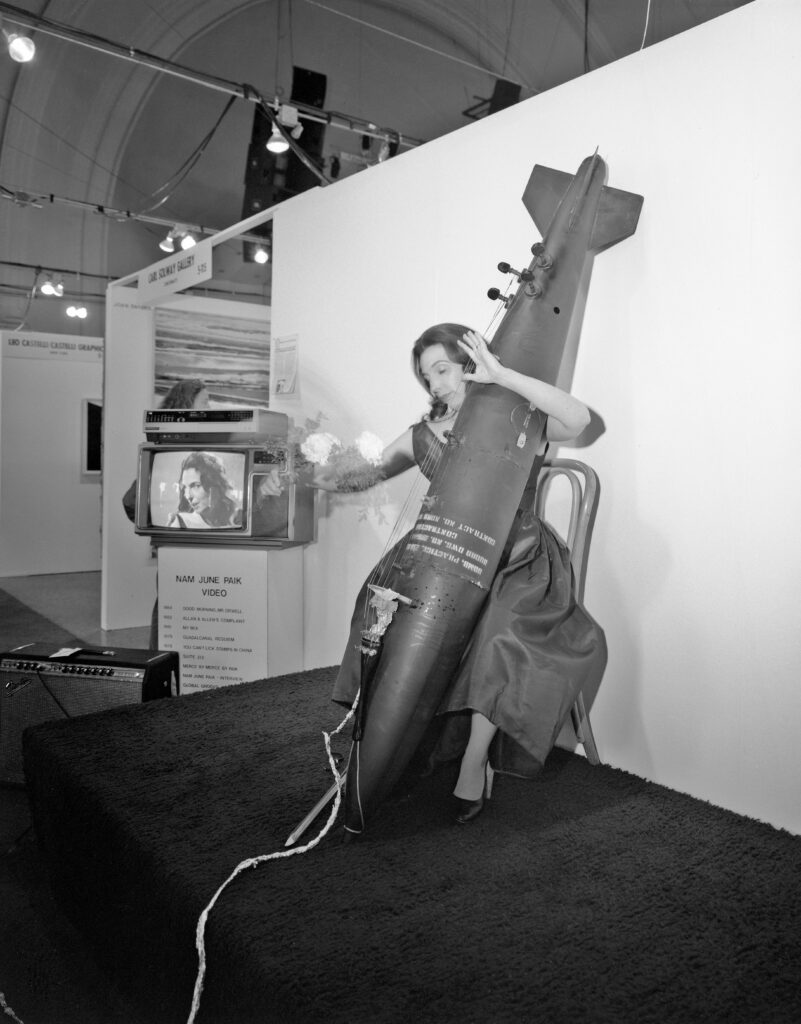

I hung out a lot with one of my very favourite people in that circle, Charlotte Moorman, Nam June’s collaborator. I have so many stories about her. I would travel a lot with them for their performances, I would run errands for them. So Charlotte Moorman was booked for The Merv Griffin Show, and the studio was somewhere on Broadway. My uncle gave me the job of bringing a 6 foot high practice bomb to the studio: Charlotte Moorman was going to play the bomb like a cello [1].

So here I am, on Canal Street, maybe I was 15 years old, standing on a street corner, trying to get a taxi holding a baby blue 6 foot bomb. No taxi would stop for me, so I ended up taking the subway and I brought it there. The show was really funny, Jerry Lewis the comedian was there, and Charlotte Moorman ended up playing the cello bomb on his back.

So hanging around Nam June Paik, I met all these different people and I was exposed to so many crazy ideas which opened up my mind. In general I’m a fairly normal person, but I probably have some weird holes in my head, from having those experiences at a fairly early age.

Nam June was very generous, and once he was well known, he wanted to give other artists opportunities. If you were an artist, that was the highest honour. It didn’t matter if you were a famous artist, or an artist working as a waiter…if you were an artist, he honoured you. I’d run into all these people who said, “Oh, Nam June gave me this and said, bring this to so-and-so, they will give you $200”. He’d create these opportunities, not just for that starving artist to get $200 (which was a lot of money in those days), but it was an opportunity for them to meet the person who was going to buy that and make a connection and do something with art.

He would be extremely generous with collaborative credits on art projects. He would make everyone an artistic collaborator. Today art has become such a business. Between Nam June Paik, Jeanne-Claude and Christo, and Merce Cunningham – that circle – it seems that they were really not thinking about money, they were just thinking about making art. That’s all they were doing, and they would pour all their energy and money into it.

“The Future Is Now” is an ambitious touring retrospective of Nam June Paik’s work, comprising close to 200 exhibits, and traveling to major museums across continents, from Europe to America and now to Asia. How did it all start, and how did things come together? Can you share with us some of the behind-the-scenes stories in the making of this exhibition? How were you involved?

Ken Hakuta: It originated at Tate Modern, but it was co-curated by Tate Modern and SFMOMA, and it went from Tate Modern to the Stedelijk, and then to SFMOMA, so it covers the beginning of Covid, the death of Covid, and the resurgence of Covid. The first show miraculously finished on February 9th 2020, just a few weeks before the whole of UK went into lockdown, and Tate Modern was closed for 8 months. It had a full, regular run.

The backers of the entire project are the Tate Modern people. The main curator is Sook-Kyung Lee, who is I would say, the foremost Nam June Paik expert in the world, aside from the old guard like John Hanhardt. Way back in 2008 or 2009, she approached me. She was a curator then at Tate Liverpool, and wanted to do a show of Nam June Paik in Liverpool. We worked with her, and she realized a very good show in 2010. Through that exhibition, I got to know Frances Morris who is now Director of Tate Modern. She was then the Head of International Art at Tate Modern, and she explained to me that the way she saw the progression of art post-1950 included Nam June as one of 5 or 6 axes through which all ideas flow. In the way Tate Modern presented art, that axis was completely missing, so she wanted to add that axis to Tate Modern’s curation.

Nam June Paik was not active in the UK at all, he had one show there in the ‘80s and after that, nothing. I started to work with Frances Morris and Sook-Kyung Lee on this project, and we came up with the idea that we would create not one, but several ‘artist rooms’ of Nam June Paik at Tate Modern, and over several years we achieved that, and that evolved into the current show, which Sook-Kyung championed throughout. It was really because of Sook-Kyung’s scholarship and interest in Nam June Paik, and Frances Morris’s belief in the importance of Nam June Paik in art history. And as it turns out, who would have known it would be one of the last great global tours just before the pandemic.

The person at Tate Modern whom I have to mention – the project coordinator – is Achim Borchardt-Hume. We would have so many fights! But I always liked Achim, we got on very well, and sadly about 3 weeks ago he passed away. He was only 55. I have to add his name because he was not just an administrator, he was an excellent curator. The exhibition at Turbine Hall now is his, and he was really, the CEO of the show. Or the Chief Operating Officer.

Later on, Rudolf Frieling from SFMOMA joined Sook-Kyung and co-curated the show. SFMOMA plays a very vital role in all of this. I really wanted Singapore to play a big role in this, because Nam June Paik has never been in Southeast Asia. I think in Asia, from what I know, there were 3 institutions that were interested: the Mori Art Museum, M+ and Singapore. I didn’t do the negotiations, but my strong preference was for Singapore.

After Singapore, “Sistine Chapel” is going to Germany, because several German museums wanted it, and they were very upset that no German museum would have a venue because in Germany, Nam June is claimed as their own [2]. The Ostwall Museum in Dortmund is going to organize their own Nam June Paik exhibition, and they want to have “Sistine Chapel” as their centrepiece.

The National Gallery Singapore promises a staggering presentation of 180 “installations, projections, video sculptures and contraptions” in its show, alongside archival material. This can be really overwhelming for visitors, especially those who may not be so familiar with Paik’s practice. In your opinion, what might be the best way to experience Nam June Paik’s work, or an exhibition of his work?

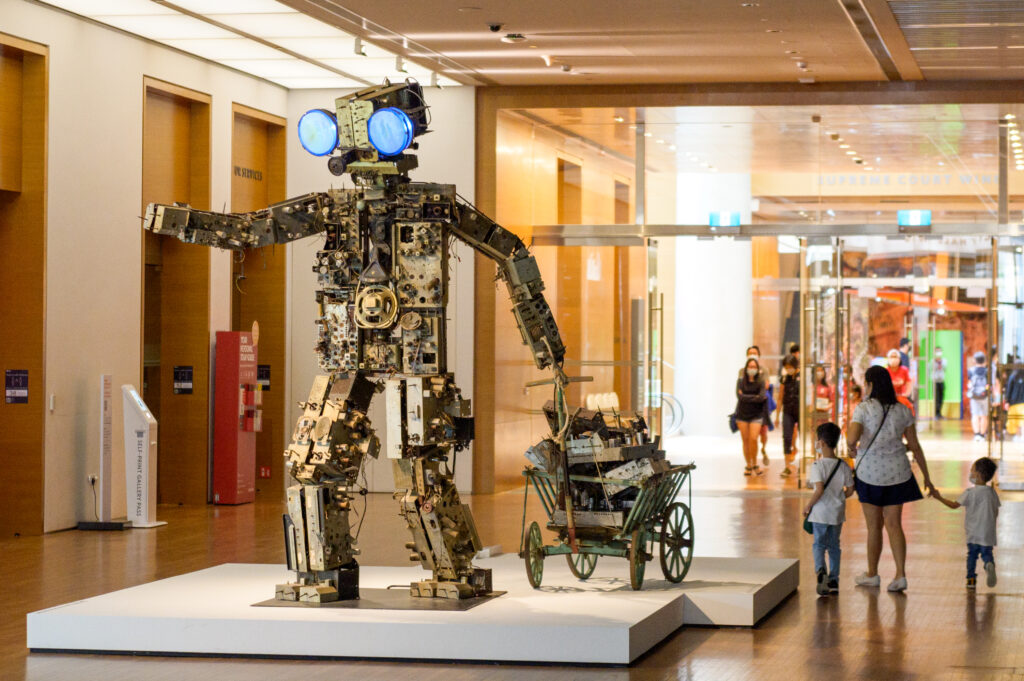

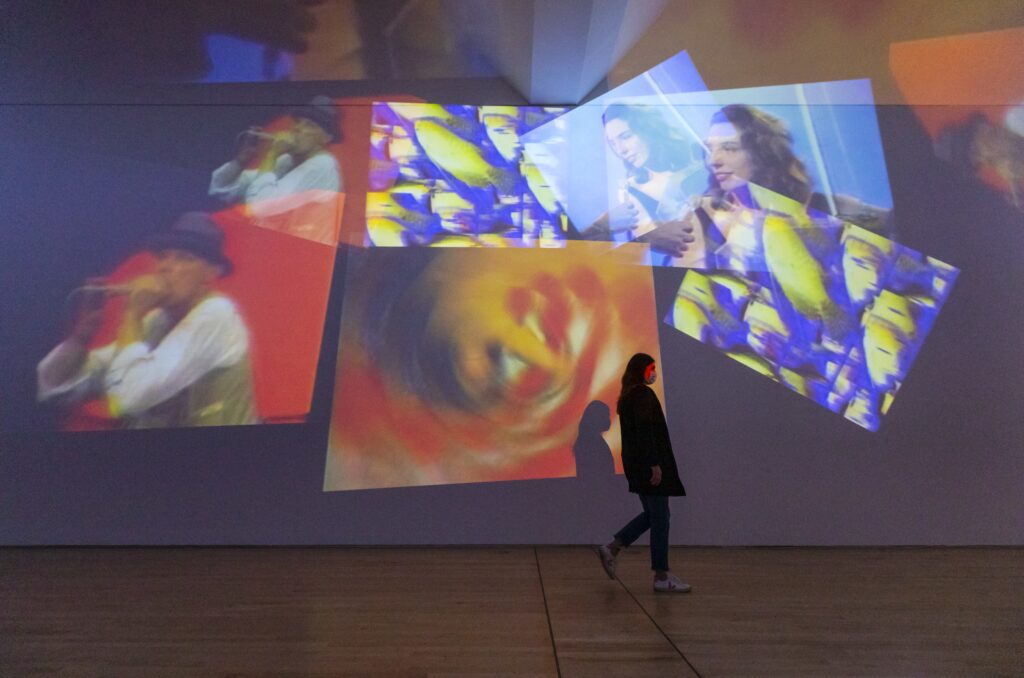

Ken Hakuta: It IS a big show. There are various aspects of it: you can see his iconic, classic pieces like “TV Garden”, “TV-Buddha” (from the Stedlijk) and “Magnet TV” (from the Whitney) and even “Candle TV”, which in all the venues, they put in the same room as “TV-Buddha” because it’s very zen-like. So that’s one way to look at it. And there are also a lot of videos you can look at, and then there’s all these cross-cultural pieces that portray parts of Japan, Korea, some parts of China, Mongolia… Nam June Paik was active for so long, from the ‘50s and ‘60s all the way up till the 21st century, so there’s a whole range and every decade is different. Then there are all these performances and paper material….

It’s daunting to do a catalogue raisonné for Nam June Paik because, what is he? A painter would be much more simple, but Nam June Paik did performances, he’s a composer who performed himself, and he performed other people’s compositions, a writer, a philosopher, a painter…so many things!

So the idea is to go in with an open mind, to embrace the complexity, and to recognize that this artist is not going to be boxed in.

Ken Hakuta: That’s right. And the works are still fresh! The ideas are still very sharp and witty, and it resonates with young people. For example at Tate Modern, they keep tabs on the young members who come, and most shows, the number of young people who come is like 1 – 2%. But Nam June’s show was 20%, it was really high. So many young people went.

The thing with technology is that it gets outdated very quickly, and a lot of Nam June Paik’s works were built on older forms of technology which are difficult to find these days. I faced this problem about a decade ago when we were installing a work by Paik from a private collection, and we had to source for CRTVs to replace those from the installation that had broken down. That was a decade ago, and already we had problems finding replacements. As the executor of Nam June Paik’s estate, what are your thoughts on how this might play out in future presentations of Paik’s works? Will there ever come a time when certain works cannot be shown anymore, simply because their components have stopped working and no replacements can be found?

Ken Hakuta: That’s a very good question and relevant to all media art, and it’s a big issue. In Nam June’s world, if he was alive, it would not be a problem because he’d just want to replace it with the latest technology, with a flatscreen or a projection.

When flatscreens came out, he spent a huge amount of money buying the big ones. That’s why he was always bankrupt! He would start asking everyone, whichever girlfriend I had, for money! And he’d say “I’ll give you credit”. Nam June Paik would have no problem replacing [the screens], but what is happening is that the museums, and many collectors, want to keep that look. There are various ways to do it: you could keep the TV box, and just replace the inside with a flatscreen, and as flatscreens change, it may just be a film in a couple of years. There are ways to keep the box and just change the projection in it. I think after the artist died, the museum world decided that they want to keep as much as possible in the original format. One way is to stockpile – we do a lot of that at the Estate – and when you can’t anymore, you just replace with a flatscreen or something like that, and that’s what we recommend too.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC have a work called “Ugly Buddha”, and it comprises one bronze buddha that Nam June made, one bronze-cast TV, and there is an actual TV. The whole thing is supposed to sit outdoors, and the idea is that the work should be exposed to nature, and over 20 years, the actual TV will rust really badly, while the cast bronze buddha and bronze TV will never rust. So that’s what it is, and at a certain point you can make the decision to maybe get a new TV.

“The Future Is Now” is an incredible project to bring Nam June Paik’s work to audiences around the globe, and a wonderful opportunity for people to experience his iconic works in person. What’s the next step for the Estate – are there certain projects you would like to see realized in the future?

Ken Hakuta: Next summer there is a very large exhibition planned in New York at Gagosian. It’s been in the works for many years. There are some objects we have never shown: we have 2 entire slabs of the Berlin Wall that Nam June decorated. They weigh 7000 pounds each.

One of the best things I did, was getting Nam June’s archives to the Smithsonian. There is so much material to get through, and the Smithsonian raises money to get it more organized each year, to fund research, and make it available to visitors.

I also endowed a Nam June Paik curatorial fellowship at Harvard University. One has graduated already, she is a media curator at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington. These are really bright curators who will be museum directors in the decades to come. This is a two-year postdoctoral programme that I’m excited about, because once every 4 years we’ll have a new scholar. They’ll be young, they’ll have all these ideas, and they will perpetuate it long after I’m gone.

If I had more energy I should work on Nam June Paik’s catalogue raisonné but he is so complex I almost don’t know how to approach it. I almost think, I should let the next generation do it, let one of the Harvard fellows start it, because it’s so complicated. If he was just an artist who did painting and sculpture that would be different. The number of installations and artworks he made is not that large; however, if you include his output in philosophy, writing, performance, composition, everything else, then it becomes enormous. And it’s very hard to record. Even the technology of how it will be recorded will have to be different too. It’s beyond me right now.

[1] A classically trained cellist who was actively involved in avant-garde art and music performances, Charlotte Moorman was one of Paik’s long-standing collaborators, with whom he created several iconic works such as TV Cello.

[2] Nam June Paik, together with Hans Haacke, represented Germany at the 1993 Venice Biennale. The joint presentation, which included Paik’s Sistine Chapel, was conferred the Golden Lion Award.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: TAN SIULI

Tan Siuli is an independent curator with over a decade of experience encompassing the research, presentation and commissioning of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. Major exhibition projects include two editions of the Singapore Biennale (2013 and 2016), inter-institutional traveling exhibitions, as well as mentoring and commissioning platforms such as the President’s Young Talents exhibition series. She has also lectured on Museum-based learning and Southeast Asian art history at institutes of higher learning in Singapore. Her recent speaking engagements include presentations on Southeast Asian contemporary art at Frieze Academy London and Bloomberg’s Brilliant Ideas series.