Home / A Conversation with ruangrupa

By Siuli Tan

There was a huge surge of collective pride in Indonesia as well as Southeast Asia when it was announced that ruangrupa had been selected to helm documenta 15. In your opinion, why do you think the time is right for a collective from Indonesia to set the direction for one of the art world’s most significant exhibitions? What shifts have you observed in the global art world that may have contributed to this?

Ade Darmawan: Socially-engaged practice, or community-based practice, has been developing for a while. We can see this back at the Gwangju Biennale in 2002, and in many alternative spaces globally. Collective practice is something that developed in the last two, three decades, but there have also been ups and downs. Like in Southeast Asia, there aren’t many (collectives) from our generation that are still alive and kicking. A lot of initiatives are falling apart, but it also shows how this practice is not supported by the whole ecosystem in many ways. But you cannot deny that there is a lot of influence from this initiative of collectives, it is rooted in a tradition of how collectives are part of the process of nurturing a certain practice towards criticality, towards artistic practice as well. If you can track back many people in Southeast Asia, many come from those roots, so it’s been very influential in many ways, but never really focused as a particular movement.

When we started ruangrupa twenty years ago we wrote a text, and there were two things that we pointed out: one is that art is becoming elitist, bureaucratic and institutionalized, and the second was that art is becoming very commodified. But if I see it right now in Indonesia, it’s even worse than that! When we wrote that, we didn’t have an art fair, but now we have two in Jakarta! [chuckles] And we have many Biennales and so on. These two decades we have so many things happening – and globally as well – and it’s much more institutionalized and commodified. I think these are factors that many people globally are also anxious about, how art is being practiced, and institutionalized. Even in Venice and documenta, there has been a lot of criticism about how it has been commercialized; even at the level of institutions like Biennales, there has been a lot of anxiety. So people try to find some other alternatives or other ways, and one of the ways is collective practice, which has struggled for many years, and maybe one of the factors that went into ruangrupa’s selection is also that we’re not just talking about it. There is a system or mechanism that we actually practice, so they see us as an entity or initiative that practices it also, rather than just discussing about it.

The selection process is really secretive [chuckles] but they see Southeast Asia or Indonesia in particular as having a really strong and rooted tradition – it’s not something coming from theory, it’s really like a cosmology, and that’s what they would like to have. And that’s also how we work, it’s coming from a different cosmology. I think they felt that they should see the perspective of other cosmologies.

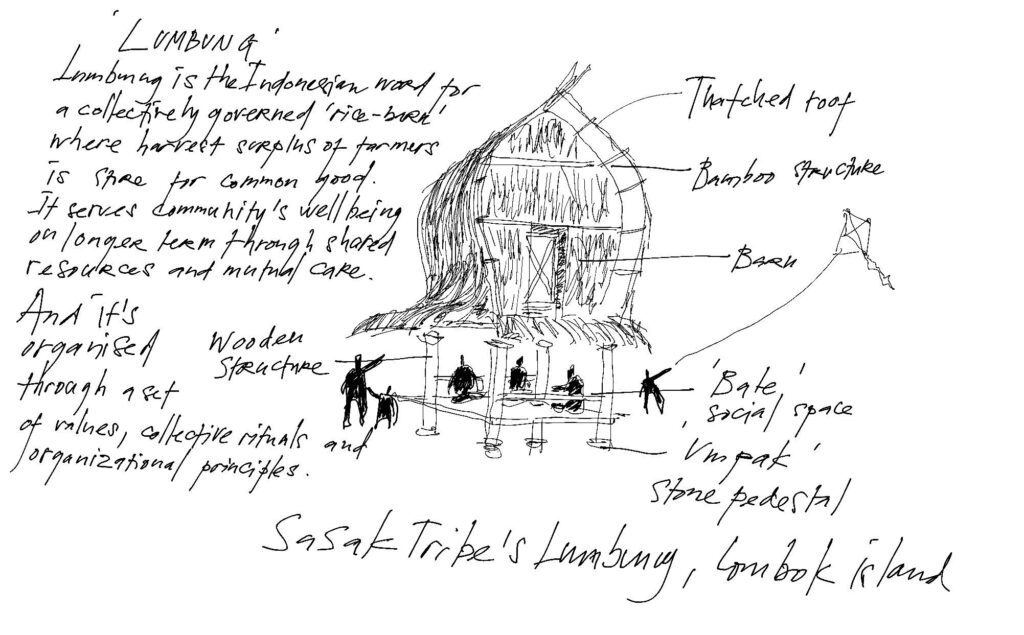

For documenta 15, ruangrupa introduced the concept of the ‘lumbung’ to underpin its curatorial vision and direction. Could you say a little more about what a ‘lumbung’ is and what it means for you, and for the approach of documenta 15?

Ade Darmawan: A lumbung is a rice barn in agricultural tradition. It’s still practiced now, in many villages, and this is also resonant with other terms and similar concepts in other places: how it’s a mechanism of collective sharing of resources, defining sufficiency, generosity and surpluses, in a cycle of agricultural tradition. But as a term or an idea, the word lumbung is also practiced in our head, how it’s actually collective shared resources — tangible as well as intangible resources that we have. In urban areas also it’s still happening and being practiced, so it’s not something exotic — we practice that as well in GUDSKUL with two other collectives, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. Since the beginning we practiced that but we never called it ‘lumbung’. In the last five years we tried to make a more systematic mechanism in how we share resources like programmes, ideas in collaboration and so on so forth, including finance. It’s also really about sustainability, ideas on how we see the sustainability of ideas, and finances.

Iswanto Hartono: Architecturally as well, the word lumbung is a practice but it’s also a very particular and specific type of architecture. And its function as well, there is one type which is used as a lumbung, as a barn; and there is one which is a social space; and the third, is a domestic and a social space. This type of lumbung is spread out over the archipelago but is widely practiced in Southeast Asia and Asia as well. This is really embedded into our daily life, and the common share, anthropologically, and the way people live in Southeast Asia and Asia, is really attached to this structure. Different places like Bali, Toraja or Sunda have different structures as to where the lumbung is located and how people work with it, but it’s very central and a very important thing for society.

Ade Darmawan: In documenta, we approach lumbung not as a theme to be illustrated or discussed, but more as a way of working or mechanism. So we created mechanisms or protocols for how to practice ‘lumbung’ in exhibitions for example, or in communication and education. It really changed how we did curatorial research as well. We don’t go around looking for one particular artwork that can illustrate the lumbung practice, it’s not about that. It’s really about selecting also how artists work: ethics, politics, and how the ecosystem works – is it collective or not. So a lot of relations have been changed as well. For example we don’t do commissions, because commissioning logic is also coming from thematic logic, and the relationship between the artist and the commissioning institution makes the artist like a service provider. We changed that, and now it’s more about intention: we all agree on a certain value, so we set up a value that we work on, and then artists or collectives work and we respect what they have been doing, and what they are doing now and what will come after. So artists continue doing what they do, which is part of our approach towards documenta. We don’t want the work to be there just for documenta — instead we try to bring documenta to the larger ecosystem, so it’s also about that relationship.

Could you tell us how the city of Jakarta has shaped ruangrupa’s mode(s) of working and strategies for negotiating the art world or art ecosystem? Did these approaches also apply in Europe when you were working on documenta, or did you have to adopt different ways of working?

Ade Darmawan: I will pick up on what Iswanto mentioned about the function and structure of the lumbung: there is a social or public function and also a living or domestic one, but also the barn or storage, which in many cultures, houses not only rice but also seeds, which is interesting because there is the imagination of sustainability. And these three functions metaphorically and practically are very interesting because this is also what we practice in our space. Our space also has these functions: a social or public space but also a living or domestic space, and then also the barn which is knowledge (artistic and so on).

In Jakarta we work spatially. We always bring this notion of being rooted in a certain locale, and then work from the space and slowly grow it with those functions. In Jakarta we really learned a lot from that and our sensitivity towards the space and the people (neighbours) as well. It’s interesting how these three functions have gone from the art institutions nowadays, or from art events even. So that’s why in documenta, we cannot avoid again to apply that by building a ruruHaus as a place that we step in from, and take root, and then slowly develop our practice through spatial sensitivity.

Iswanto Hartono: How did Jakarta shape ruangrupa? In the case of Indonesia, Jakarta of course is a very postcolonial city in terms of development. If you see, historically, we never had strong urban planning development, especially during Suharto’s time. During the time of the Dutch Batavia had a very strong planning approach, for the benfits of the colonial empire, and during Sukarno’s time, his approach was very locally-rooted, with national monuments as well as with very European sensibilities, with the plaza etc. He wanted to build the grand era of a European city in Asia, using all the symbols of imperialism but changed to national symbols of Indonesia. And it changed again during the New Order regime, where urban development was very much attached to the political and economic interests of the regime, which do not belong to the people or culture.

ruangrupa always rented houses in the beginning due to the outcomes of this kind of development where there are no resources for the people or culture: everything is for economic or political reasons, so in terms of the unconnected city developments as you see, and with a transportation system that was built for the benefit of the car industry, not for public transportation. Hence, ruangrupa works in between, dealing with leftover, neglected urban spaces. We never worked ‘large’, we always worked closely in the neighbourhood, with society, with a space under the highway bridge for instance with our first mural project. And as you know we don’t have infrastructure for culture, and we have to really struggle. Our approach is really embedded with the city, and here in Europe, we already tried several approaches with our previous work with using intervening spaces like what ruangrupa did in Jakarta, and it was well applied in places like Japan, Sao Paolo, and in Sonsbeek as well where we built ruruhuis. We don’t want documenta to be like an alien spaceship, so ruruHaus is one of the projects we started in documenta 15 to be more locally anchored, with plans to sustain it after documenta, so it’s just the beginning. What we will offer is not commission-based works, but shared spaces.

ruruHaus is a small ecosystem within the larger documenta and within Kassel, and this is how we work and sustain based on mutual partnership and sharing. Everybody sees documenta as a kind of funding body as well, but we try to flip these expectations and see what will happen.

Ade Darmawan: We changed a lot of relations. Even for Kassel, like Iswanto mentioned, people see documenta as a big UFO coming every five years, sucking the energy and resources and then it’s gone. It’s really amazing how it’s exploitative in many ways, and this also happens in many events in different parts of the world. So being there with ruruHaus lets us see Kassel as a local, and we can bring them in conversation also with other locals. Working with artists there and so on so forth, they’re pretty surprised that this has never happened before. Many approach Kassel like a blank sheet, like a big white cube, whereas for us we don’t work like that, we see it as a place with people and stories and histories. Maybe it’s rare for Artistic Directors to hang out with people! Artistic Directors are always like in a cloud…but now (people) can always just come to ruruHaus and hang out with us. It’s a very different relation.

How have your interactions with Kassel’s artistic and creative communities played out? What has ruangrupa learned from this preliminary process that can be or will be taken into the exhibition itself?

Iswanto Hartono: It’s very important to change the perception of the documenta brand, which is that it’s for the local ecosystem as well, not just for the artists who come. As Ade said, since the previous edition lots of exploitation is happening. How we approach the people of Kassel is also important. If you are just one single person or Artistic Director it is really hard to meet people. But as a team we have more time to meet people to talk and build relationships. There are limits of course, but through discussion all the time and giving them a platform in ruruHaus to empower and to change, there are other ways to work in a big festival rather than just to commission for example. It’s more about mutual sharing, and that’s how we work and we did it already with ruruhuis in Sonsbeek. We always try to improve on what we did, and in Sonsbeek I think we did not have a strong interaction because we did not stay that long, but now we are here in Kassel for a longer period of time. Everyone has been flying in and out — so there will always be a few members of ruangrupa here. Connection is very important to open up, as are relationships and sustainability. We are always thinking about how to sustain together, and thinking of economic models, as well as models for relationships and sharing.

Ade Darmawan: There’s a lot happening already in the Kassel ecosystem. I think this has to do with how globally, this kind of big event has to do with politics and local politics and how the city government or the state sees the event as a gentrification strategy and also a strategy for city branding, economic development etc., which is more or less the same as how politicians or corporates see such an event. So it’s not something specific to documenta: we can see this happening also in many places, the ignorance of such an event or institution towards their own local resources, and there’s also fear, so we can see how we can develop that to change the relationship and also the way how the people and the city see or perceive such an art event. Many of our events are supposed to be a bridge to embrace certain localities, and of course documenta and us are not the only ones to deal with such an issue. Previous curators and Artistic Directors also tried to do that: Ruth Noack tried to do that by having a free ticket for everyone in Kassel, so it’s always an issue of how to communize documenta, Because it is a big resource, how to manage it and how to become part of benefitting the locals is always a challenge.

Iswanto Hartono: The strategy from us to work with the city space here is one of the translations of how we try to organise the whole event within the structure of the city. For example we reached out to the part of the city which has very rarely been used for documenta before. Kassel is divided by the Fulda river in the centre, and after the Second World War, development in Kassel was scattered and imbalanced. Now we try to reach out to the east, we are trying to shift the centre of documenta towards the east which is a more industrial and neglected area. The advantage for us is that we came from Jakarta, so it’s easier for us to work here than for someone from Kassel to interface in Jakarta. I can imagine it will be so difficult. For us, working in Jakarta which is so complicated with so many social layers and political issues…it’s not to say that it’s easy in Kassel, but we worked with so many more difficulties within the scale of Jakarta, so for us to do an intervention here is more manageable.

Ade Darmawan: To add as well, it’s always a question how an event can be extractive, and most of the exhibitions have this mode where we bring everything, everyone into one place, so our big question that we always address during this process is: what’s the meaning? (Of being in Kassel.) It should be mutual, rather than just bringing a translation from one practice in Africa, for example, to Kassel. What does that mean and how can the resources cycle back to where it came from? So this is also one thing that we address and challenge also, for artists and also for Kassel. Artists are starting to come in, and so there’s collaboration and connection, so hopefully we can see this cycle happening because many big events suck everything in a self-centred way and are centred in one particular place in time.

What can visitors to documenta 15 expect to see or experience? Can you share some of the projects or artworks that we can look forward to?

Ade Darmawan: It’s going to be more than an exhibition, more than just artworks as we know it. There are a number of artists who are not working in a single way or with a single sensibility, but also ignite other sensory experiences with gatherings, with education, with events, with music, performances and so on. There’s going to be a lot of that as well — experience-based artistic approach, not only static exhibitions. There’s going to be a lot of workshops, classes, conferences…there are several models of education, of knowledge sharing practice, and also gathering, a social gathering mode, like kitchen, eating…that kind of stuff. It’s really also related to what we’re doing, which is inspired by how we live in the place, in Jakarta, in Southeast Asia. There is no such thing as ‘one exhibition’ only, there’s always some music, gatherings, karaoke…it’s like the distinction of exhibition and non-exhibition…It’s not that we don’t believe in that, we believe it should be more than only an exhibition, more than only that kind or that way of making artistic or knowledge experience.

It also has something to do with how we perceive this as not to do with a ‘theme’. If we go that way it really changes also the artists and collectives we are interested in or inspired by. Many artists working with object or production-based approaches are very centralistic, and how do they share that with others? It’s going to be very problematic for artists who work that way. Maybe you also saw we announced the artist list, and how we formed many majelis (cosmologies). [The artists] opened a forum for collaboration amongst themselves and self-organized their collective thought.

There’s going to be a different way of how we deal with the audience – we approach it more as a hosting approach, rather than ‘public education’ or to ‘educate them’. I think people will hopefully experience a lot and also learn from each other, because that’s also how we approach collective or artistic practice: it should be mutual, and also many times why we select one practice is because we are inspired by them, and we can learn a lot from them as well, so there is a lot of admiration as well in the whole thing. But I don’t think there’s going to be monumental artworks. Traditionally documenta will have that, a big sculpture… but I don’t think we’re going to have that kind of spectacle. It’s going to be more horizontal than phallic, not like flexing or showing it’s a big exhibition…We don’t go that way.

Iswanto Hartono: In the beginning we decided already we were not going to have any artists with towering budgets or works which are very much more than the others, so we are not going in that direction. We are always a bit sceptical about the distinction between ‘high art’ and ‘low art’ and we always make fun of it with our works previously, and here as well we try to blur these things. We are trying as well to be as transparent as possible, with the exhibition-making as well, so opening up the process for visitors to be able to see this. For example with production, we work with several organisations on sustainable materials for example, involving lots of upcycling materials, and even with artists’ production as well, so it’s not so much on objects or things but more on how to bring out the process and awareness to be tangible for the visitor. So there are multi-layers of projects, and there’s always a question that comes to us: where is the art, and what kind of art will it be this time?

Ade Darmawan: And also in terms of the city, because of the nature of the artists and collectives that we involve – that they work at different sites and in different ways– it will exist in several places or even move around ephemerally. I think it’s going to be blurry between art and life, because a lot of practice is also about that, this connection between art and life. As blur as possible would be great.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: TAN SIULI

Tan Siuli is an independent curator with over a decade of experience encompassing the research, presentation and commissioning of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. Major exhibition projects include two editions of the Singapore Biennale (2013 and 2016), inter-institutional traveling exhibitions, as well as mentoring and commissioning platforms such as the President’s Young Talents exhibition series. She has also lectured on Museum-based learning and Southeast Asian art history at institutes of higher learning in Singapore. Her recent speaking engagements include presentations on Southeast Asian contemporary art at Frieze Academy London and Bloomberg’s Brilliant Ideas series.