Home / Exhibition Review: “NAM JUNE PAIK: THE FUTURE IS NOW”

National Gallery Singapore

10 December 2021 – 27 March 2022

Organised by Tate Modern, London and San Franscisco Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with National Gallery Singapore.

Curated by Sook-Kyung Lee (Senior Research Curator, Tate) and Rudolf Frieling (Curator of Media Arts, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) in collaboration with curators from National Gallery Singapore, June Yap (Senior Curator), Clarissa Chikiamco (Curator), Jennifer K. Y. Lam (Assistant Curator) and Roy Ng (Curatorial Assistant).

By Tan Siuli

Nam June Paik: The Future Is Now – a major retrospective of the visionary artist’s work – has opened at the National Gallery Singapore, at the end of a two-year global tour. The exhibition comprises close to 200 exhibits, spanning installations, sculptures, paintings, drawings and archival material. This will be the first time that such an expansive and ambitious presentation of Paik’s oeuvre is presented in Southeast Asia, and offers audiences an unparalleled opportunity to experience several of his iconic works in person.

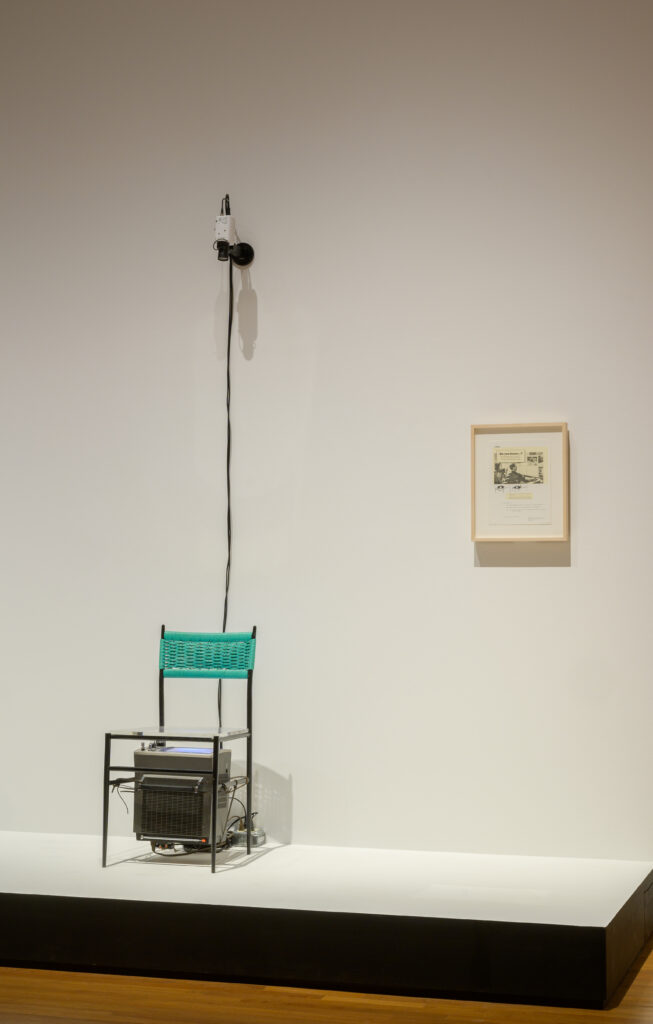

Hailed the “father of video art”, Paik was a visionary in several ways and this retrospective demonstrates how much of his work was clearly prescient of how technology would become enmeshed with our daily life and sense of self. “TV Chair” (1973) for instance, explores notions of surveillance and self-regard with a good dose of humour. Trained above a chair, a CCTV camera (technology which is now ubiquitous in our lives) captures images of the viewer, which are then relayed via a television placed under the clear seat of the chair, presenting a catch-22 where it is impossible to see yourself (hence satisfying our inherent narcissism or sense of curiosity) and be comfortably seated at the same time.

Another work, “Global Groove” from 1973, foresaw the era of global communications and mass media, where access to cultures and happenings around the world can be immediately accessed on screen. “Global Groove” splices together footage from several sources, subverting the notion of a unitary image or stream and introducing a dizzying collage of sounds and visuals to viewers – a precursor to Netflix channel-surfing and mashup culture. Here, place, space, and even time are collapsed and compressed in a bewildering simultaneity of flickering images. This torrent of imagery, deliberately distorted by Paik’s editing, bears a striking resemblance to the pixelated images occasionally encountered during streaming, or to the ‘poor image’ [1] trawled from the internet, a marker of our post-digital age with its multiple channels of image circulation and (re)distribution. True to the exhibition title, the ‘future’ that Nam June Paik foretold, is our ‘now’.

Given Paik’s legacy as a pioneer of video art, it is perhaps unsurprising that the exhibition at the National Gallery plays up the promise of “a riot of vision, colour, and sound”. This sensory assault and deluge of imagery is indeed present in a number of works in the show, notably in Paik’s iconic “Sistine Chapel”, his work for the German Pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale which immerses the viewer in a barrage of images and sound from Paik’s past works, hence drawing parallels between this overwhelming audio-visual experience with the sense of awe and wonder viewers of yesteryear must have experienced upon encountering Michelangelo’s frescoes in Vatican City.

While many of Paik’s biographies emphasize his role as an innovator of video art, less is made of his lifelong interest in Buddhist principles, and this exhibition goes some way towards exploring this strand of his thinking and practice. Notably, in contrast to the technicolour graphics advertising The Future Is Now on promotional banners and material, the exhibition opens with an austere, monochromatic tableau that has only the slightest intimation of animation. Paik is introduced in this first gallery via a winking, black and white portrait, a small black and white performance video, and the work “One Candle (Candle TV)”, (2004). This introductory gallery sums up much of Paik’s playful experimentation and his twin interests in Zen and technology. The candle in the television set alludes to TV’s flickering screen as well as the idea of constant flux and change; as an object of our gaze it refers to the practice of meditation as well as our more mindless visual fixation on ‘the goggle box’.

The nod to Zen Buddhism is signposted throughout the exhibition, by way of seated Buddhas either collected or sketched by Paik, and of course the quintessential Paik work that sums up the dialogue between ‘East’ and ‘West’, ‘spirituality’ and ‘modernity’: “TV Buddha” (1974). It is also present, in a lesser-known gem of a work titled “Zen for Film” (1964), Paik’s homage to John Cage’s groundbreaking “4’ 33”” (1952). Cage’s composition directs performers not to play their musical instruments for the entire duration of the piece, and the work is comprised entirely of silence and / or ambient sounds, challenging conventions of music and performance. Paik translated this score into a blank film projection on a wall: in “Zen For Film”, there is nothing to see except for a rectangular patch of projected light in a 4:3 format, flickering and grainy, with the occasional silhouette of a gallery-goer animating the piece. As with Cage’s work, ambient sounds and sights – or what would normally be regarded as disruptions or incidental noise – become part of the work, which is realized differently in every iteration. “Zen For Film” also recalls “Candle TV” introduced at the start of the exhibition, suggesting a similar state of ‘blank’ staring at a glowing screen. While some may read into this work a certain iconoclasm or an ‘aesthetics of boredom’, “Zen For Film” also evokes the Buddhist concept of sunyata, or emptiness. Created several decades ago, this work’s ideas are still fresh even till today, in its challenge to conventions of the medium, and in playing up the medium’s materiality and exhibitionary context. Fortuitously for audiences in Singapore, the exhibition Orchestral Manoeuvres at the Art Science Museum [2] presents a number of sound works by artists responding to John Cage’s ideas as Paik did, as well as contemporary artists questioning the conventions of medium and how it may be ‘performed’ or subverted in the way that Paik questioned the film medium [3].

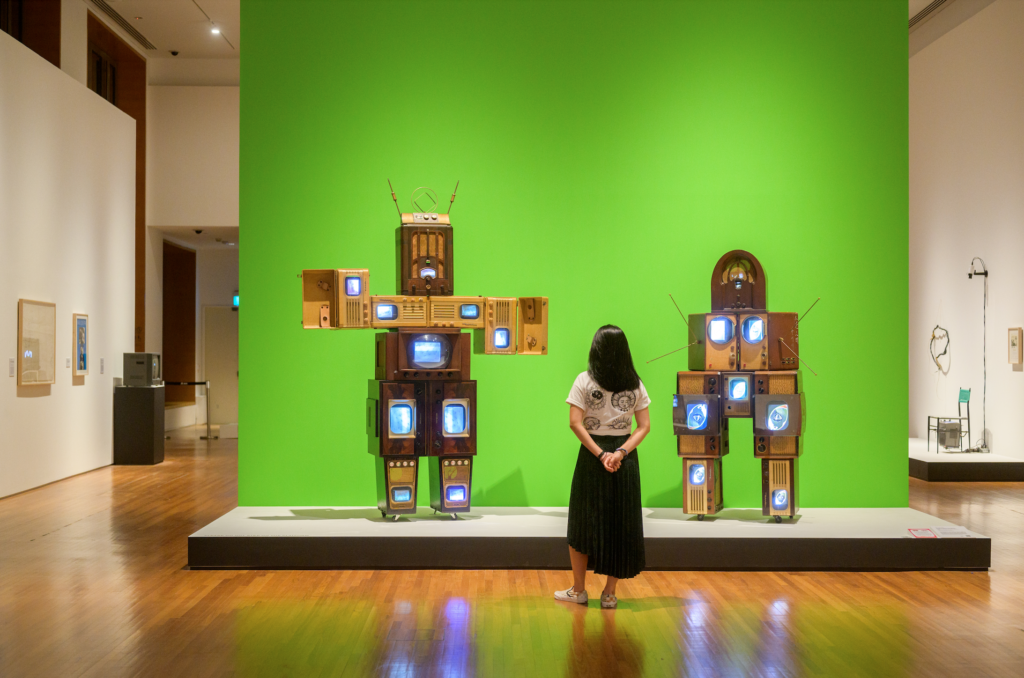

“Zen For Film” is but one of a number of works in the show that look at Paik’s circle of friends and collaborators, and how they may have influenced and shared ideas with each other. Paik was actively involved in the Fluxus movement, and one receives the impression that he shared warm friendships with many of his artist friends, as evidenced in his numerous collaborations (with Charlotte Moorman in particular), and in the works he dedicated to them, or in which he acknowledged their influence. “Zen For Film” aside, Paik also created giant robots dedicated to John Cage and his legacy, as well as an elegiac scroll in memory of Moorman after her death from cancer. These tributes reveal a generosity of spirit, and several passages in this exhibition reveal how Paik’s work and world comprised of and intersected with that of several other individuals.

The sheer breadth of material presented in The Future Is Now clearly shows that Paik was more than just a video artist. Archival materials, as well as a lesser known ink work on paper demonstrate that he was a performance artist as well as a consummate painter. In addition, he was also a composer and a philosopher. The variety and liveliness of his output testifies to the dexterity of his thinking and artistic expression, and in many ways his practice exemplifies the Zen adage of having a ‘mind like water’ (mizu no kokoro): fluid, flexible, constantly in motion, flowing around objects and ideas with ease, and into the furthest reaches. The flow of water is an apt metaphor for the torrent of images that we receive through his work and by which Paik heralded the age of “the electronic superhighway”, but it is also expressed in the fluidity and openness of the metaphors he employed in his work. Like a Zen koan, these are expressed directly and with a playful economy of means, but the avenues for transformative understanding that these visual koans open up are vast and limitless, triggering multiple questions and ideas in quick succession like a set of Chinese boxes springing open. Take for instance his work “Zen For TV” (1963), in which the artist repurposed a spoilt television by turning it onto its side to create a sculptural artwork, transforming the blue line across its screen – an indicator of its malfunction – into an expression of zen-like minimalism, inviting parallels with the sublime stripe paintings of Barnett Newman. Decades on, Paik’s works continue to inspire with the wittiness and dexterity of their ideas, inviting audiences and new generations of artists to unpack and reflect upon them anew, in relation to contemporary life and culture.

[1] The term ‘poor image’ was coined in 2009 by artist and media theorist Hito Steyerl, to describe digital image copies (often of poor resolution or quality) that proliferate on the internet. These images are often displaced from their original contexts, and repeatedly edited and re-edited, and circulated in new permutations, hence reflecting a shift in how images are used and apprehended in contemporary visual culture.

[2] Read ART SG’s review of the exhibition here– Exhibition Review: “Orchestral Manoeuvres: See Sound. Feel Sound. Be Sound”

[3] Hong Kong based artist Samson Young’s Muted Situation #5: Muted Chorus for instance, features a choir in performance, but it is absent of music: instead, it records incidental noises such as the rustle of scoresheets, and the singers’ drawing and hissing of breath, making heard the (often) unheard.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: TAN SIULI

Tan Siuli is an independent curator with over a decade of experience encompassing the research, presentation and commissioning of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. Major exhibition projects include two editions of the Singapore Biennale (2013 and 2016), inter-institutional traveling exhibitions, as well as mentoring and commissioning platforms such as the President’s Young Talents exhibition series. She has also lectured on Museum-based learning and Southeast Asian art history at institutes of higher learning in Singapore. Her recent speaking engagements include presentations on Southeast Asian contemporary art at Frieze Academy London and Bloomberg’s Brilliant Ideas series.