Home / Exhibition Review: “Orchestral Manoeuvres: See Sound. Feel Sound. Be Sound”

ArtScience Museum

28 August 2021 – 2 January 2022

Curated by Adrian George and Amita Kirpalani

By Tan Siuli

I agreed to review an exhibition on sound art with some reservation, having attended all too many presentations of this genre where the visitor experience is generally quite sterile, comprising mostly of shuffling from one headset to another, or jostling with other visitors to stand under the ‘sweet spot’ of a sound dome to fully experience a work. Most of the time I leave such exhibitions with a vaguely disembodied sensation, the paucity of visual or otherwise sensorial engagement leaving much to be desired. Happily, Orchestral Manoeuvres at the Art Science Museum in Singapore upended my presumptions, and most unexpectedly, moved me to tears.

Bringing together works by 32 artists and composers from across the world, Orchestral Manoeuvres explores the spectrum of artworks and projects that engage with sound and how we might experience it, conceive of it, and create it. The exhibits span some of the earliest forays in musical notation from the Schøyen Collection of manuscripts, to notable contemporary works that have been presented extensively around the globe, and which audiences are now fortunate to be able to experience in Singapore.

Opening the show, in a section titled ‘Resonance’, Hannah Perry’s sound installation Rage Fluids sets the tone for the exhibition. Copper-coloured metal sheets curve around the gallery, activated by speakers concealed behind. The growl of the subwoofers builds up to a roar, and in doing so, creates vibrations along the length of the metal sculpture. This is a fully embodied experience: as the viewer walks into the spaces and folds of the sculpture, s/he is able to viscerally experience the resonance from the surrounding metal sheets. At the same time, the reverberations create shudders and ripples along the length of the metallic surfaces, warping and dissolving reflections and a sense of the space. The work’s serpentine form simultaneously recalls the adrenaline-fuelled culture of car modification and race tracks, as well as the sensuous curves of the human body; as an opener, Rage Fluids is a dramatic work that delivers on the exhibition’s premise of seeing sound, feeling sound and being sound. To reiterate this point, a suite of prints by Carsten Nicolai located close by, captures the effects of sound waves on a container of milk, the rippling patterns making visible the invisible: a visual echo of the vibrations experienced bodily when in proximity to Perry’s installation.

Orchestral Manoeuvres has been conceived of as a blended soundscape, and sure enough, on the aural margins of the hum and thrum emitted by Perry’s sculpture, one can vaguely discern a persistent clinking sound. This comes from a neighbouring gallery titled ‘Sounds Around’, which is also an extension of a section on ‘Performing Objects’. Here, quotidian items have been orchestrated into assemblages that recreate familiar soundscapes, as in Hsiao Sheng-Chien’s evocation of sounds from his childhood. Nearby, Singapore artist Zul Mahmod has configured a smaller, framed iteration of one of his iconic works: an abstract grid of metal pipes fitted with mechanisms that strike the pipes at intervals to create a percussive composition.

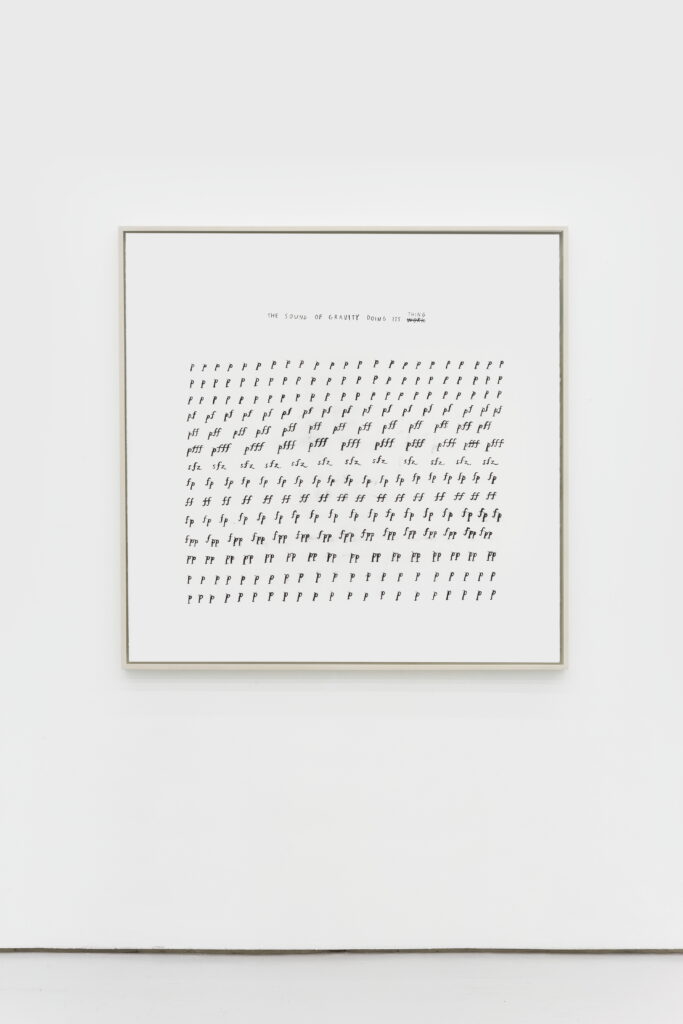

As a counterpoint to this sonic landscape, the works of Christine Sun Kim and Idris Khan within this same gallery introduce ideas about scoring sound, translating the audible into (silent) written form, and the sensorial into the abstract. Deaf since birth, Kim visualises sound through her own idiosyncratic scoresheets comprising a series of repetitive symbols with slight (and humorous) variations, their handwritten appearance conferring the impression of an intimate and highly personal system of notation. In a similar way, Khan’s magnificent prints are also about a negation of sound. From afar, they appear as abstract, gestural scribbles, echoing Kim’s handwritten notes; up close, the prints reveal themselves to be a palimpsest of musical scores, overlaid so that they almost cancel each other out, or conversely, attempt to capture the multidimensional complexity of an orchestra in performance.

This segues nicely into the next section where (Western) paradigms of musical performance, composition and notation are explored, and questioned. Singapore artist Ang Song-Ming transforms the five-lined stave manuscript into an abstract canvas, echoing Khan’s visual explorations in the previous gallery. Alternative musical ‘languages’ and approaches to scoring are also explored, for example in John Cage’s experimental and unorthodox performances, as well as in Japanese artist Toshi Ichinayagi’s vertical notation. A set of historical manuscripts from the Schøyen Collection, ranging from the oldest-known score from Babylon, to Vedic chants and koto music notation, resonates with some of the experiments undertaken by the artists featured in this gallery.

The ideas explored in Cage’s ground-breaking 4’ 33” — which made peripheral noise and audience participation part of the work — are extended in several other pieces featured in the exhibition. Samson Young’s Muted Situation #5: Muted Chorus features a choir in performance, but it is absent of music: instead, it records incidental noises such as the rustle of scoresheets, and the singers’ drawing and hissing of breath, making heard the (often) unheard. Other exhibits comprise purely of written instructions that invite the viewer to realise the artwork, often solely within their own imaginations or in a state of contemplation. Yoko Ono’s Earth Piece for example, asks viewers to “Listen to the sound of the earth turning”, and in an adjacent gallery, Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations invite each of us to tune into ourselves in an act of ‘deep listening’.

The next gallery moves adroitly from such abstractions to offer audiences glimpses of how each and every one of us connects with sound (and performance) in a very personal and relatable way. The faintly wistful strains of The Smiths’ ‘Stretch Out And Wait’ drifted over me as I entered a darkened gallery, coming face to face with a young man singing karaoke earnestly. Filmed in Indonesia, Phil Collins’s dunia tak akan mendengar documents fans of The Smiths performing various songs from their 1987 album “The World Won’t Listen”, and the gamut of individual expression chronicled here ranges from raucous fun to melancholia, perfectly encapsulating the heartfelt connection each of us makes with a piece of music. Continuing this theme is Gillian Wearing’s Dancing in Peckham, which depicts the artist dancing unself-consciously in a busy London mall to her own private soundtrack, bringing into focus notions of public versus private experiences of music.

Arguably the highlight of the show, Janet Cardiff’s The Forty Part Motet comes towards the end of the exhibition, and occupies an entire gallery on its own. Photography and mobile phones are discouraged to facilitate full engagement with the experience that this installation offers. The work is a choral performance of a piece of Renaissance sacred music; forty speakers are arranged in an oval, with benches placed at their centre, and each speaker plays a recording of one individual voice. Visitors can sit at the centre to listen to the voices in unison, or choose to listen closely to each individual voice by walking up close to each speaker. The result is a powerful and inexplicably moving experience of choral music. Perhaps someone more familiar with music theory might be able to better analyse the effect of this work – I had been told, beforehand, how people have wept in its presence, and as I sat in the centre of that circle of speakers, allowing the music to wash over me, I found tears streaming down my face. Enough superlatives have been lavished on this work during its prior iterations in Europe, America and Canada; suffice to say, this is a work that reaches towards the sublime, and reaffirms the transcendent power of sound, and of art.

Perhaps the exhibition’s organisers felt that after such an incandescent experience, some ‘grounding’ would be necessary for visitors as they exit Cardiff’s gallery. The ‘Decompression space’ that follows invites visitors to reflect on the works in the exhibition, and features an assortment of interactive and educational exhibits and activities. After the transports of the previous gallery, this felt like a comedown. Cory Arcangel’s playful recreation of a musical masterpiece by Arnold Schoenberg (featuring a collation of cat videos culled from YouTube) might have fared better if encountered earlier on in the show, reinforcing the iconoclasm and experimental spirit of other works explored in previous galleries. Encountering it after Cardiff’s work is almost a descent into bathos.

On the whole however, Orchestral Manoeuvres is a well-paced show, engaging and accessible while introducing a breadth of ideas about and around sound and sound art, with rich resonances between works. Curated to mark the tenth anniversary of the Art Science Museum, the exhibition rightfully deserves its place as a highlight on the arts calendar this year, and offers visitors a treasured opportunity to encounter some iconic works of art that I believe, in time, will be considered contemporary masterpieces.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: TAN SIULI

Tan Siuli is an independent curator with over a decade of experience encompassing the research, presentation and commissioning of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. Major exhibition projects include two editions of the Singapore Biennale (2013 and 2016), inter-institutional traveling exhibitions, as well as mentoring and commissioning platforms such as the President’s Young Talents exhibition series. She has also lectured on Museum-based learning and Southeast Asian art history at institutes of higher learning in Singapore. Her recent speaking engagements include presentations on Southeast Asian contemporary art at Frieze Academy London and Bloomberg’s Brilliant Ideas series.