EXHIBITION REVIEW: “STORIES ACROSS RISING LANDS”

Museum MACAN, Jakarta, Indonesia

23 January – 23 May 2021

Co-curated by Aesep Topan (Museum MACAN) and Jakarta-based Korean curator Jeong Ok Jeon

By Sadiah Boonstra

Aptly titled, Stories Across Rising Lands offers a variety of artist perspectives on the historical and geographical diversity of Southeast Asia. As Museum MACAN’s first-time ever collaboration with an external curator Jeong-ok Jeon, a long-time Jakarta-based curator originating from Korea, the exhibition provides a balanced geographical and topical spread. Eight artists and one artist duo offer unique, historically, socially, politically specific and localized perspectives of lived realities across Southeast Asia.

An important element in the exhibition is the pertinence of history, legacies of history, and its entanglement with the present throughout Southeast Asia; four artists place history at the heart of their works. In both The Pass and the Present from Each Either Side of the Wall. Endless Story #1 and The Pass and the Present from Each Either Side of the Wall. Urban Story #1, Myanmar artist Nge Lay merges two photographs, each from a different time and place. One is an old black-and-white photograph or postcard, while the other is a contemporary colour photograph created by the artist. The artist then layers the photographs so that the past and current photo merge to the point that they become hard to distinguish. The works reveal our inability to fully comprehend either past or the present, yet simultaneously foreground that past and present are entangled. Similarly, Cian Dayrit’s, Ain’t no other way out of this shitshow (2020) offers many historical layers to unpack, such as colonial history and its legacies in the Philippines, but the focus of this work is the fate of the Aeta indigenous community. The artist’s embroidery over a colonial photograph of an Aeta circle dance taken by American zoologist, Dean Worcester (1866-1924) is a comment on Aeta’s current struggles for land rights. As such, embroidered tree stumps are a raw reminder of ecological degradation and a reference to Aeta’s ancestral lands being stolen.

Artist Eko Nugroho at his studio in Yogyakarta, Indonesia © Eko Nugroho

Two artworks are concerned with historical legacies in Indonesia. Saleh Husein’s Arabien Controlled Territory (2018/2021) consisting of video, archival documents, and text on wall, explores how the Dutch colonial government constructed racial categories to exercise control in Indonesia. The story of the little-known topic of the ‘Kapten Arab’, Arab captains, in charge of Arab communities under Dutch colonial rule, is set against a poetic video of continuously washing and retreating shallow waves that never hit the beach. It addresses the role of Kapten Arab in the emergence of an anti-colonial movement under influence of pan-Islamic thinking in the early twentieth century. The display includes Raden Saleh’s painting Javanese Mail Station (1879) which can be viewed as a reference to colonial control as the work depicts part of the Jalan Raya Pos (Great Post Road), a massive infrastructural project that was crucial for empire building. Moving to contemporary history, the 1965 mass violence that marked the transition to power of Indonesia’s second president Suharto (r. 1966-1998) lies at the root of Hikayat Wanatentremor Tale of Wanatentrem (2018) by Maharani Mancanagara. Her storybooks and rotation boxes, working like rolling scrolls, are created both for children and adults. Allegorical characters like a mouse deer, wolf, sheep, pirate, and birds relate the lives of a number of political prisoners of the 1965 events who were exiled to the island of Buru. In a tactile way that might even be interpreted as a longing to move away from media technology, Mancanagara makes a silenced past playfully accessible.

Saleh Husein, Arabien Controlled Territory, 2018/2021, video and text on wall, Variable dimension, Collection of the artist, Image courtesy of Museum MACAN.

Maharani Mancanagara, Tale of Wanatentrem, 2018, Story books in Indonesian, Korean Language and English inside rotation boxes, vitrine, acrylic on wood, charcoal on wood, Collection of the artist, Image courtesy of Museum MACAN.

Obviously, there are other concerns in the region, which take the form of a video. Engaging with capitalism and its social consequence are Ho Rui An’s installation and video Screen Green (2015/16) and Knit (2018) a performance by Kawita Vatanajyankur. As a one-hour lecture Screen Green is a clever comment on the tension between the politics of greening in Singapore through green screen post-production; on which any political imagination can be projected. Vatanajyankur uses art as soft power to voice social concern for female labour and the exploitation of the fast fashion industry. In her performance, as a human knitting machine, Vatanajyankur uses her mouth and other body parts to knit a piece of garment in 25 minutes, the timeframe within which Thai factory labourers supplying for the fast fashion industry have to produce one piece of garment. Yet another video work by Souliya Phoumivong’s Flow (2018) reflects on the tension between individual identity and societal norm in a playful stop motion video about a boy who is accepted into a buffalo herd when he puts on a buffalo mask, but singled-out as an outsider when he takes it off.

Kawita Vatanajyankur, Knit, 2018, Video documentation of performance, Collection of the artist, Image courtesy of Museum MACAN.

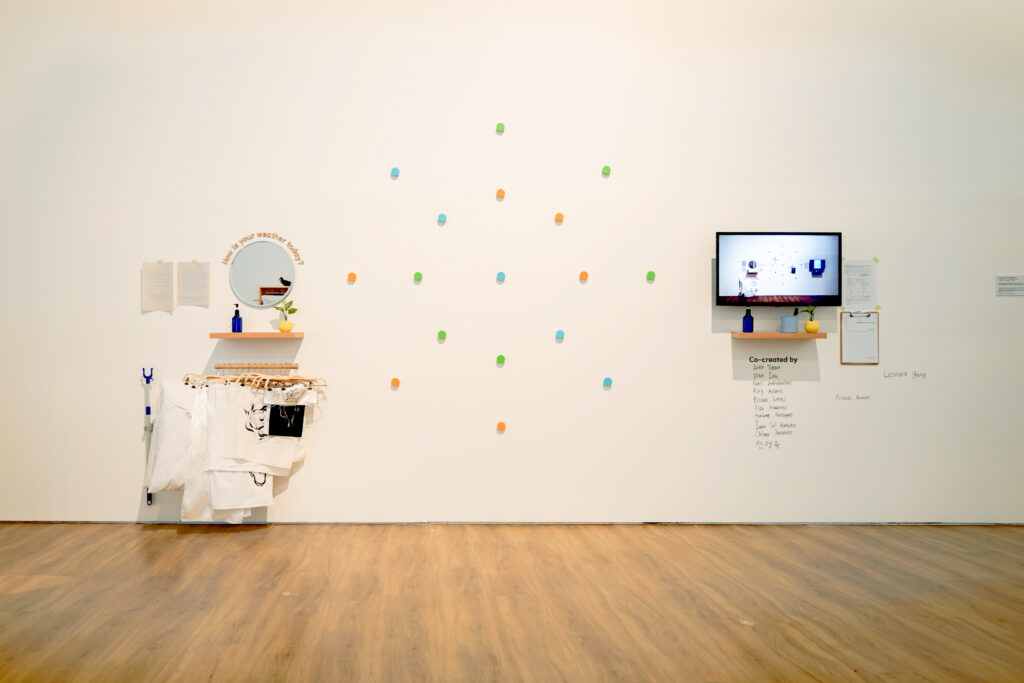

The interactive installation [re-enacting memories] with you (2021) by Tan Vatey and Sinta Wibowo brings us back to the lived realities of the pandemic. Based on the notions of togetherness and trust, the work invites the visitor to reflect on their mental well-being during the pandemic by asking ‘How is the weather today?’ The visitor is encouraged to express their state of being by picking fabric pieces that each symbolize a different state – a pillow stands for spiritual, a handkerchief symbolizes personal feelings, and a towel refers to a practical state of being – and hang them on the wall. Every time a visitor changes a fabric in the installation, a different constellation emerges which can be interpreted as a reflection of the current state of being of Museum MACAN’s visitors. It is a loving attempt at giving solace and support during these difficult times, and a reminder that we are in this together.

Tan Vatey & Sinta Wibowo, [re-enacting memories] with you, 2021, Wooden text, mirror, hand-written letter, hand sanitizer, indoor plant, wooden shelf, wood stick, grabber, hanger, various fabrics (scarf, handkerchief, pillowcase & pillow, flag, bath towel, kitchen towel, face mask), TV, photo slideshow, black marker, Collection of the artist, Image courtesy of Museum MACAN.

The pandemic resulted in a revaluation and recreation of Lim Kok Yoong’s Licensed to Wait (2015/2021) as notions of waiting, patience, and anticipation for future activity, have become burning. Lim visualized the process of waiting as two empty chairs in a fishing set-up with nothing else to look at than a video projection on the floor that changes shape and images, recalling the image of water ripples. While the body is currently unable to travel, the mind can wander to places in anticipation of what in future might again be possible.

Cian Dayrit, Ain’t no other way out of this shitshow, 2020, Embroidery, objects and digital print on fabric, Collection of the artist, Image courtesy of Museum MACAN; Lim Kok Yoong, Licensed to Wait, 2005/2021, Installation and video projection, Collection of the artist, Image courtesy of Museum MACAN.

As the exhibition was curated and held during the pandemic, the show is accompanied by a number of videos presented by curators Asep Topan and Jeong Ok Jeon that give insight into the artists’ broader artistic practice and contextualize the works on display. These videos enable an understanding of the works without having to physically visit the exhibition. In times of a pandemic, it is mandatory that the intended interactivity of the works cannot be fully sensorily enjoyed, but in some instances media technology enables the imagination of the sensory experience of the work; Mancanagara’s work, for example, is accompanied by a video that narrates the story and shows how the story boxes are manually rotated.

Needless to say, it is impossible to capture the many social, political and cultural diversities and, in some cases, piercing economic disparities of Southeast Asia in a single exhibition. Stories across rising lands is clearly aware of the regional complexities and succeeds to highlight poignant urgencies of the region through artists’ perspectives. Each work in the exhibition, though historically and locally specific, can be regarded as a window through which various lived realities can be explored that are pertinent across the region in times of a pandemic.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: SADIAH BOONSTRA

Dr Sadiah Boonstra is a curator and historian living and working in Jakarta, Indonesia, with over a decade of curatorial experience. Formerly Sadiah was Asia Scholar at Melbourne University/Curator Public Programmes Asia TOPA (Melbourne) and Senior Programmer at National Gallery Singapore (Singapore.) Her exhibition projects include a number of international exhibitions amongst which are Framer Framed in Amsterdam (2020,) Galeri Nasional, Jakarta (2017,) Erasmus Huis, Jakarta (2015, 2017,) British Museum, London (2016,) Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam (2008.) In her broader cultural practice Sadiah combines academic expertise with curation, public programming, producing, and teaching. Her professional and research interest focus on the arts, heritage, and history of Indonesia.