Home / Exhibition Review: “The Gift”

Museum MACAN, Jakarta, Indonesia

23 January – 23 May 2021

Co-curated by Aesep Topan (Museum MACAN) and Jakarta-based Korean curator Jeong Ok Jeon

By Elaine Thanya Marie Teo

In the basement of National Gallery Singapore lies a curio of an exhibition presented by Singapore Art Museum (SAM). The Gift, the result of an ongoing transnational collaborative project — Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories, is a subtle study in the confluences of relations and how they manifest across geographical borders. The project involves institutions from Singapore (SAM), Indonesia (Galeri Nasional Indonesia), Thailand (MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum), and Germany (Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). This grouping was brought together by the Goethe-Institut in 2017, to create a dialogue between the collections of the four institutions around their common interest in contemporary Southeast Asian art. The Gift is one of four exhibitions planned for the culmination of this collaborative endeavour. Quite unlike the status quo of a single travelling exhibition, Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories frees the curatorial team (compromised of SAM’s June Yap, Galeri Nasional Indonesia’s Grace Samboh, MAIIAM’s Gridthiya Gaweewong, and Nationalgalerie’s Anna-Catharina Gebbers) to embark on four interrelated exhibitions. According to Yap, the genesis of the collaboration started in 2017, and the curators found their discussions shaping up to a focus on exhibitions.

On the slate of exhibitions, The Gift debuts right after MAIIAM opened ERRATA in Chang Mai, with Nation, Narration, Narcosis by Nationalgalerie due to open in November 2021 in Berlin, and The Acquiescent Allies by Galerie Nasional Indonesia rounding off the project in early 2022 in Jakarta. The weight The Gift carries in terms of expositional elements is significant and runs the danger of being overly didactic. However, what is borne out in SAM’s temporary exhibition space at National Gallery Singapore, is a quiet focus on the delicate strands of interweaving histories, and networks of intersecting ideas.

Seemingly modest in its curatorial framework but ultimately carrying a sharp riposte to conventional ideas of artistic exchange, The Gift takes its departure point from Korean American artist Nam June Paik’s recollection of his first meeting with Joseph Beuys in 1961. These two towering figures in the art world would go on to develop a close friendship and engage in a series of projects together right up to Beuys’ death in 1986. The Gift uses this artistic exchange as a lens to consider meaning-making behind institutional collections. The exhibition steadfastly and somewhat admirably refuses direct threads of attributing the encounter of Southeast Asian artists with Euro-American ones as the catalyst for artistic movements. This strategy of demurring from easy generalizations, is exemplified by the use of Joseph Beuys’ Energiestab (Energy Staff) to lead visitors into the main exhibition space. Shamanism was a shared interest between Beuys and Nam June Paik. The Energiestab (1974) epitomizes Beuys’ preconceptions of shamanistic practice with its roots stemming from the oft-repeated tale of his rescue from a plane crash while serving in the Luftwaffe regiment in 1944. The myth goes as follows: somewhere around Crimea, a group of Tartars pulled Beuys out of a plane crash he was in. They nursed him to health by rubbing fat on his body and wrapping him up in felt. Energiestab itself is composed of copper and felt, two materials Beuys would refer to as crucial in the idea of healing and spirituality. In truth, the highly exaggerated tale exposed Beuys to the critique of being a mere confectioner by art historian Benjamin Buchloh, in a scathing rebuke published in Art Forum’s 1980 January issue.

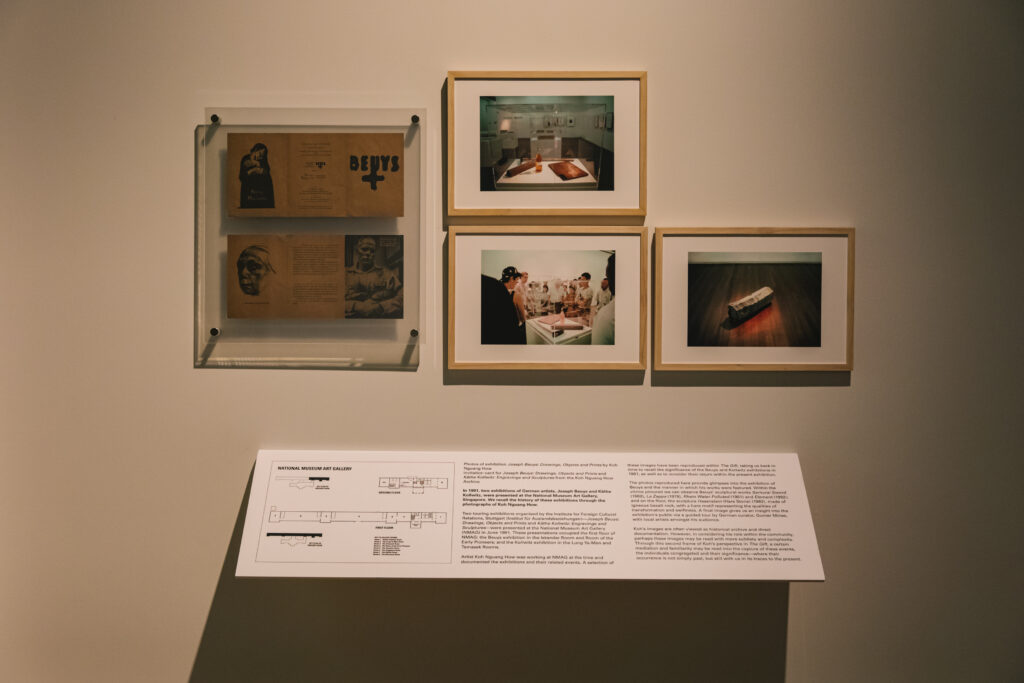

Along with her institutional counterparts, June Yap’s curatorial eye lays bare Beuys’ Energiestab (Energy Staff) for audiences to consider Beuys’ influence across geographies. Positioned in a nook and directly across from Koh Nguang How’s documentation of two travelling exhibitions of Joseph Beuys and Käthe Kollwitz held in Singapore in 1991, Energiestab can be read in a multitude of ways. The absence of any explicit link to Joseph Beuys’ artistic practice with his regional counterparts in terms of art production within the exhibition is a particularly strong undercurrent. Instead, what we are presented with is something a lot more nuanced and restrained. Koh, as part of the National Museum Art Gallery (NMAG, the predecessor to SAM and National Gallery Singapore), documented this exhibition of Beuys’ and Kollwitz’s artworks, and the audience who consumed this aesthetic display. Nestled in one of the photographs alongside the 1991 exhibition invite, is a photo depicting German curator Gunter Minas leading a tour surrounded by local Singaporean artists. In the photograph, the curator has his eyes trained on a vitrine featuring Beuys’ Samurai Sword (1982), Rhein Water Polluted (1981), and Element (1982). Of all the artists appearing in the documentation listening closely to Minas, Tang Da Wu, a seminal figure in contemporary arts in Asia and beyond, is unmistakably present.

“The entanglements are there”- June Yap

Beuys’ influence in art history is such a dense minefield that the decision to gently sidestep this influence and instead present it as a touch point for local and regional art communities is deft play by the curatorial team. June Yap further points out that these images from the 1991 exhibition serve as a strategy towards “triggering [these] memories” from the local communities to examine a particular period in the nascent contemporary arts scene in Singapore and Southeast Asia. The mirroring quality in the display of Koh’s and Beuys’ works serves as a rich entry point into the exhibition proper, with its dispersed idea of artistic influence and inheritance.

In the main exhibition space, visitors are greeted with Tang Da Wu’s Monument for Seub Nakhasathien (1991). Drawing ever so slightly from Tang’s presence in Koh’s photographs, we encounter a work almost captivating in its simplicity and unpretentious scale.

Displayed without a plinth (a mode of presentation explicitly rejected by Tang in SAM’s communication with the artist), the sculpture, made of wood and plaster sits soberly on the exhibition’s floor. Rather than crafting a straight line between Tang and Beuys (a curatorial entry point made possible given Tang’s performance art background), Monument for Seub Nakhasathien expands the idea of exchange inwards within Southeast Asia. Nakhasathien, a Thai ecological conservationist, succumbed to death by suicide in 1990 after a lifetime of campaigning passionately for environmental sanctuaries in Thailand. Tang’s own oeuvre has centred on themes of the ecological and the social world. His seminal works, Tiger’s Whip (1991), and They Poach the Rhino, Chop Off His Horn and Make This Drink (1989), examine the poaching of wildlife with a raw intensity. Monument for Seub Nakhasathien differs largely from this approach. The general idea of a monument, as one typically outsized, contrasts with the quiet presence of this tribute. The work hints at how shared ideas travel across Southeast Asia and speak to one another.

Perhaps the clearest line linking aesthetic practices occurs in the decision to place Ahmad Sadali’s Gunungan Emas (The Golden Mountain), 1980 side by side with Salleh Japar’s Gunungan II, 1989-1990. The symbolism of mountains in the Nusantara region carries heavy spiritual weight, taking Beuys’ apparitional ideal of Eurasian mysticism further into a more grounded authentic realm. The gold leaf overlay in Sadali’s Gunungan Emas explores how the elemental idea of the spiritual endures in time immemorial, working similarly with Beuy’s Energiestab, 1974 and its copper construction. Though no definite connecting line or relationship exists between these artists, the curation highlights recurring motifs as well as shared interests.

Moving to Japar’s Gunungan II, we see an artist building upon this symbolic imagery of mountains and expanding the compositional field to countries as diverse as Indonesia, Australia, Thailand, and Myanmar. Japar’s inclusion in The Gift and the intimate space that the exhibition devotes to his 1993 artwork, Born Out of Fire undoubtedly calls to mind the ground-breaking 1988 Trimurti exhibition held in Goethe-Institut Singapore. The exhibition involved Salleh Japar, Goh Ee Choo and S. Chandrasekaran as young upstarts who bypassed their graduation show at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), and instead mounted an interdisciplinary exhibition in the Goethe-Institut. Once again, the long-intertwined history of institutional engagement becomes hard to avoid.

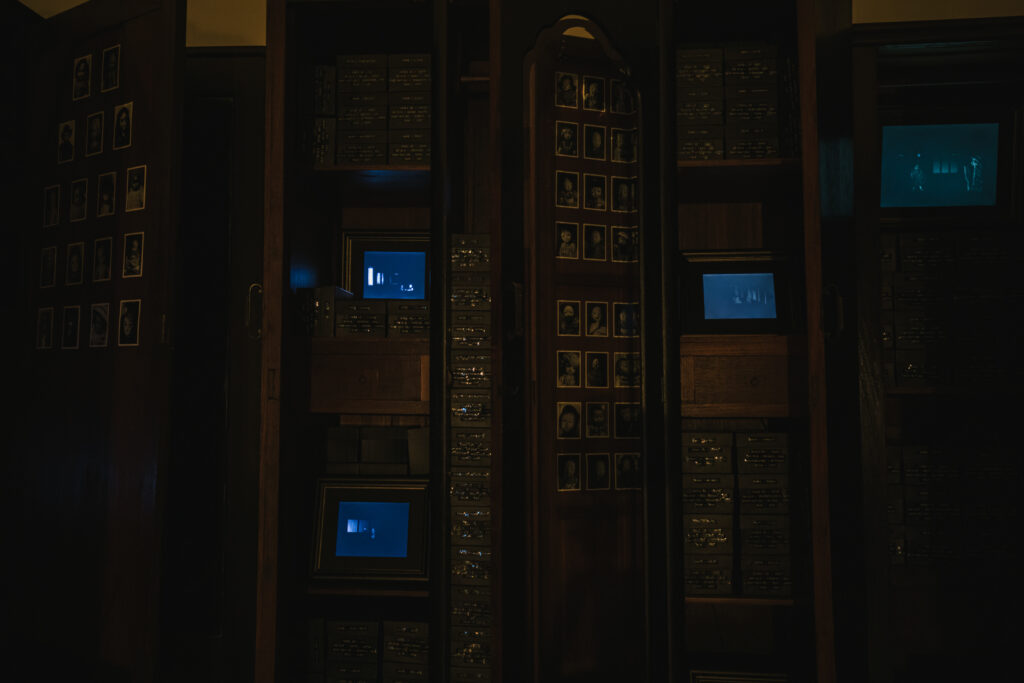

The exhibition’s closest approximation to the concrete idea of global exchanges occurs in Donna Ong’s The Caretaker (2008), which weaves a fictional setting around the Friendship Doll Project, a cultural gift exchange programme initiated by American missionary, Reverend Sidney Gulick in 1927. Amidst rising tensions as a result of the 1924 Immigration Act passed by the United States Congress that severely limited East Asian migration, Gulick organized for a set of blue-eyed dolls to be sent to Japan as a gesture of goodwill. Japan responded in kind with its own set of kimono-clad dolls sent to the United States. Ong’s installation occupies a sizable portion of the exhibition, second only to Ampannee Satoh’s The Light (24:31), 2013. The cavernous quality of the archival setting adds a fitting backdrop to the images of the deteriorated dolls, creating a sense of ominous foreboding. Considering where history leads US-Japan relations in World War II, the installation adds to the careful reserve of the curation. Ultimately, Ong’s inclusion highlights the sheer impossibilities involved in calculated exchanges across history and geographic boundaries.

What The Gift offers is a slow burn into the idea of convergences over artistic expression, and transnational exchanges. The tangents deriving from initial encounters with the other are never served up neatly for audiences to consume. The exhibition proposes a studied look at diffused networks of relations within the region and Euro-American world. For all its restraint and elusiveness in rejecting firm intersecting lines across geographies, one does wonder about the limiting parameters of this attempt. Working with Goethe-Institut as its unifying facilitator and having each national collection bound by its own remits, the subtlety perhaps belies the very roots of the exhibition’s genesis. The Gift requires visitors to slowly come around to the idea of institutional collection narratives functioning at the mercy of different tangents occurring concurrently, including that of cultural policies and aspirations; it is an exhibition that requires several visits to fully comprehend and unpack the intricacy of global exchanges. The only thing that no repeated visit can tell us quite yet is whether this inter-institutional collaboration is going to be sustained, and how it might affect artistic and cultural exchanges in the years to come.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: ELAINE THANYA MARIE TEO

Elaine Thanya Marie Teo is a writer, and researcher based in Singapore. She holds a MA in Asian Art Histories from LaSalle College of the Arts, and a BA in Psychology from Nanyang Technological University. Her research has focused on the intersection between identity, and the visual arts with a particular eye towards deconstructive theory. In 2017, She served as a panellist in Singapore’s Third Graduate Conference in Visual Culture. She was also a speaker at the State University of New York’s Art Conference in 2018. As part of Tekad Kolektif, Elaine Thanya Marie Teo is the 2021 recipient of the Objectifs’ Curator Open Call.